Tax belongs to everyone, and there’s a special place for ethics within it. The relationship is twofold: we expect the law itself to be fair in its setup and effects, and we expect taxpayers to have a fair attitude towards it.

The Archipel Fair Tax Mark pertains to that latter element. We seek to establish as objectively as possible something that is subjective by its nature: does a company have a fair attitude towards its taxes, and does it approach those public duties ethically?

In this paper, we give a brief history of Tax & Ethics, elaborate on our own view on the topic, and demonstrate how we’ve created an ‘objective test’ of whether a company’s policy is Fair in that sense. Godspeed, reader!

Methodology

For the Fair Tax Label, we will assume the law itself to be Fair, and public institutions equally so. This means that taking a straight path in applying the law is virtuous, and so is being transparent with the relevant information and compliant with reporting requirements.

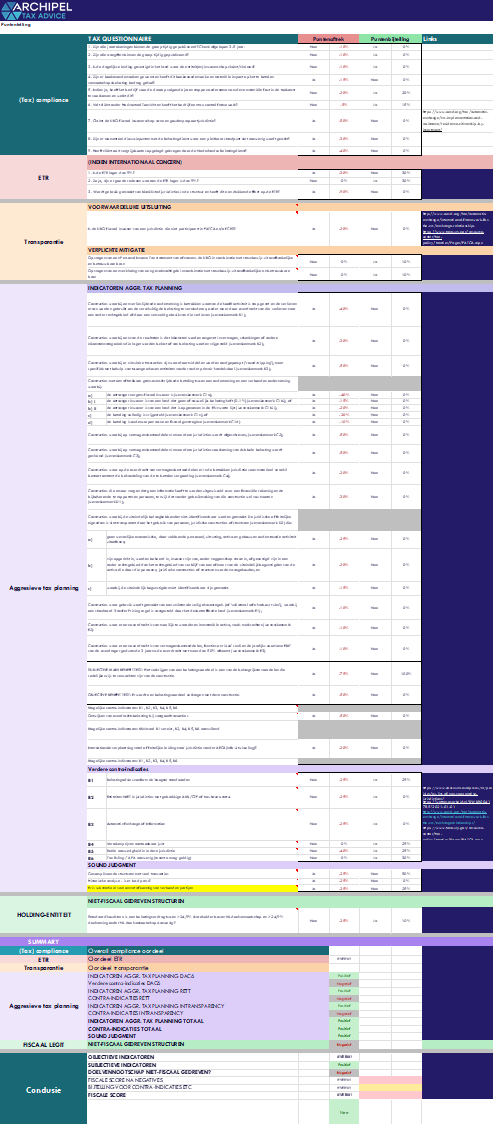

In order to establish this, we test certain elements:

- Tax Compliance: timeliness and completeness of statutory and tax filings, UBO transparency and residency, and Tax Authority Disputes;

- Effective Tax Rate: does the companny or group pay a ‘realistic profit tax’ as compared to the statutory profit level, and any blacklisted jurisdictions involved with an ETR-mitigating effect?

- Transparency: do the UBOs reside in FATCA/CRS participating jurisdictions and do they properly report and pay their Personal Income Taxes?

- Aggressive Tax Planning: does the group or company meet, without mitigation, any of the OECD’s Hallmarks of Aggressive Tax Planning?

- Tax Driven Structure: is any top holding entity interposed for treaty reasons?

Based on the above, a compounded eagle-eye view of the Fairness of any company’s Tax Attitude can be distilled methodically:

The factors were selected to form a congruent test that measures adherence to the spirit of:

- FATCA/CRS [UBO compliance];

- The OECD’s BEPS-Project [minimum tax rates and currency of compliance], and;

- DAC6 [hallmarks of aggressive tax planning].

Based on the above, we can test whether a company is generally transparent about its performance and ownership, subject to an overall fair tax rate and current on its payment obligations, and ‘Fair’ in its attitutes towards tax structuring and ‘organicness’ of paths.

Why the Orangutan?

The Dayak people of Borneo have a myth that the Orangutan was originally a man, who pretended not be able to speak. They are considered strong and highly intelligent animals with a great ability to think, but keep to themselves because if they were ever caught, they would be forced to get jobs.

In the sense of a Fair Tax Mark, we like to think that the Orangutan sits quietly and passes judgment. Rather than get involved in the discussion on what is fair and what isn’t, our Orangutan tests our behaviors against our own logic and gives us a thumbs-up or thums-down. With the infinite wisdom of the rainforest behind it, we can only accept its verdict rather than argue it.

Make the Orangutan happy or get forced to work and do better!

Why do I want a Fair Tax Mark?

A Fair attitude towards tax is part of any full-scope ESG policy. Taxes are part of the very fabric of civilization, and any societal license to operate includes an obligation to live your taxes in fairness. With our comprehensive test, we refrain from judgment about Tax Fairness itself and consider this the legislator’s domain, as the spearhead of the democratic process. However, we do analyze how you interact with your taxes, and whether your policies are cooperative, transparent and non-agressive. We build on objective analyses already built by the international community [mainly the OECD’s Inclusive Framework] and therefore project broad-based consensus on the selected sub-tests.

Obtaining a fair Tax Mark demonstrates that you perceive taxes not just as a cost to be minimized, but as a matter of good citizenship and solid stakeholder management, balancing between the company and its owners, the society within which it operates, and the governments that manage that.

For more background on how we see ‘Fairness in Taxation’, we refer to the white paper below!

White Paper –> Tax and Ethics: an Evergreen Topic

In music, an evergreen is a hit that remains relevant over time. “All I Want for Christmas is You” returns every Christmas. “Greased Lightning” and “Paradise by the Dashboard Light” are sung along at every party during that tedious fifteen-minute intermezzo. “Lose Yourself” is played before every sports final… For an artist, scoring an evergreen means striking oil, but the Evergeen itself can become a chore to the artist. Bobby McFerrin once revealed in a 2013 interview with USA Today regarding his evergreen “Don’t Worry, Be Happy”: “I got tired of singing it – I sang it millions and trillions of times…”

Well, taxation also has its evergreens and ‘ethics in taxation’ is definitely one. The theme recurs periodically, each time reflecting the latest views on ethics in society. These often evolve faster than the legislative process can create new laws, introducing an intertemporal element to the conversation. And said conversation is often held between a larger group of socially engaged but less fiscally initiated individuals on the one side, and a smaller group of nerded-out but socially more detached technicians on the other. Adding an inter-expertise element to the talk.

The topic of ethics often flares up when governments need revenues, when an election is approaching, or when figures on wealth distribution and purchasing power are published, sometime with a little engineering. And often, the same scene occurs: the non-tax expert rides into the conversation on a noble horse wielding news reports and an ethically sharped sword of the accusor, while the tax expert dons a shield of tax-technical and oftedn outdated counterarguments, asserting that there is nothing illegal in the stories, that ‘the news’ presents an incomplete or biased picture, or that ‘things are different now anyways’. Both actors have a point, but they do not connect.

In order to build a Fair Tax Mark that uses measurable and objective criteria to discern whether a company’s tax setup is fair, we must clean the conversation of too many moving targets and create a photo of what we consider markings of ethical tax behaviors and unethical ones. And that first means we should properly discern between fairness in tax policies [public] and fairness in tax strategies [private]. An honest attempt:

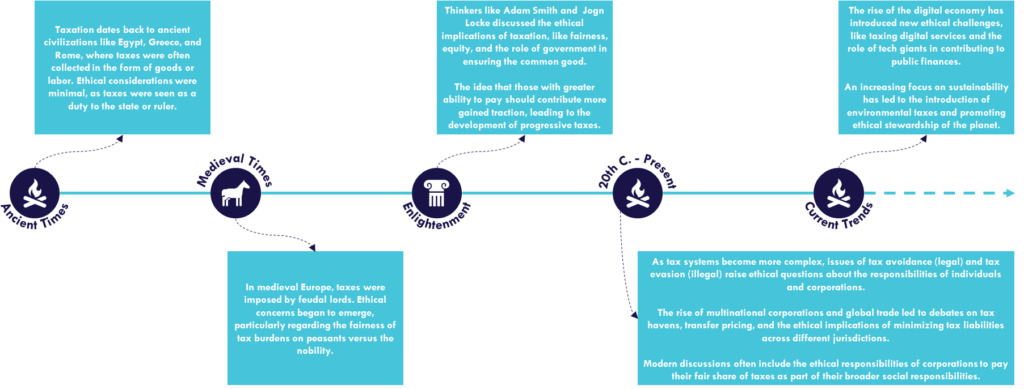

A brief history of Tax & Ethics

Discussing ethics in taxation is a luxury, reserved for advanced civilizations. For instance: in ancient and medieval times, taxes were decreed by rulers without ethical considerations. It wasn’t until late-ancient Greece, Egypt, or Enlightenment Europe that taxes were discussed ethically, and that people considered a society’s taxes find justification in their fairness. Even today, plenty places don’t facilitate any public discourse on taxes and ethics. Thus, having Ethics in Taxation as a topic is a privilege, deserving a well-rounded and respectful approach:

The amount of papers published on Tax and Ethics follows a hockey stick growth path. The topic becomes more prevalent as globalization increases and tax competition between nations as a result of it, while awareness of public spending and social mobility grows.

As it stands today, Tax & Ethics is a regular part of the curricullum at most any University that provides a Tax Law or Tax Economics program. The Maastricht University is an example, and our own Rolf Gelissen teaches said class there:

Rolf, you teach the “Responsible International Tax Planning, Compliance and Administration” class at Maastricht University. Why was this class added to the curriculum?

In the past, how much tax companies (and hnwi) paid did not have much public interest. As a result of the financial crisis in the beginning of this century, governments had to ‘bail out’ several big multinational corporations. As tax money was used to ‘save’ these big corporations, journalist and a bit later later also ‘the public’ became more and more interested in whether companies where indeed ‘paying its fair share of tax’. For the university this public debate on ‘paying your fair share of tax’ and the corresponding ethical aspect of doing so, was for them the reason to add the ethical component to the legal aspects of (nternational) taxation.

by now, however, the ethical discussion is not only focusing on the tax payer (and whether he or she is paying its fair share of tax.). It has been extended to aspects like government spending (“is your government ding the right thing with your tax money” or are they wasting it?) and the ongoing discussion about harmful tax competition between countries (is a country showing “ethical behaviour” towards its treaty and / or trade partners).

What is the objective of the class?

The main purpose is to create awareness that in the current world, taxation is not only about applying the rules (i.e. the tax law and the treaties). In order to do this I like to discuss fiscal ethics from three different angles: 1) ethical tax behavior from tax payers towards society, 2) ethical tax behavior from the government towards its tax payers and 3) ethical tax behavior between jurisdictions.

How would you differentiate between ‘Fair Taxation’ at a public policy level, and running a ‘Fair Tax Policy’ as a private company or institution?

Unfortunately I can’t give you an answer to that question. What I learned from my students discussing tax and ethics with them is that “showing tax ethical behavior” (both for tax payers as for the government) and whether you are paying your ‘fair share of taxes” can differ depending on time and place.

A student once made the following remark: A speed limit on the road is a maximum speed, not a minimum. It can’t be guaranteed that you will always be able to drive at the speed limit. Depending on time and place, the right thing to do may be to hit the brakes and drive at lower speed.

Assuming however living and operating in a democracy with a non-corrupt government, it is (in my personal view) initially your (legal) obligation to apply the (tax) law.

But that does not mean that you can’t fight the law if you don’t agree with it. Protest, go to court or go into politics. Or migrate to a different country.

Many thanks!

Tax Fairness versus Fair Tax Policies

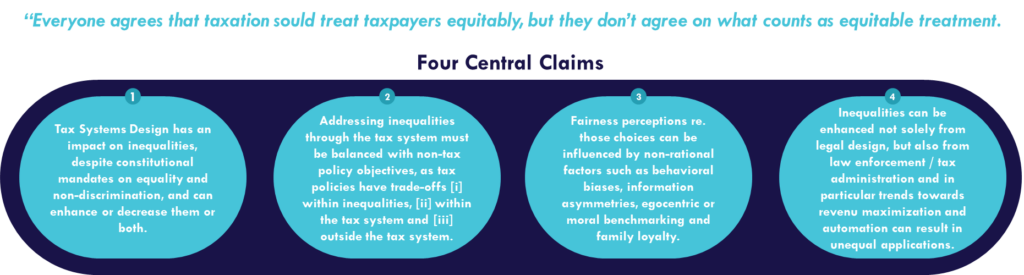

In the context of a Fair Tax Mark, it is important to discriminate between literature and thought catalogs about Fairness Taxation, which would discuss mainly how public tax policies have fair objectives and results, and those about Fairness in Tax Attitudes, which pertain to how taxapayers and specifically companies approach their tax strategies and what role tax ethics play in that.

Fairness in Taxation has become a prominent topic in at least the European public debate, especially after the financial crisis. The term is often used in political discourse due to its intuitive appeal and pro-social connotations, but its vagueness makes it problematic from a normative perspective. For such a normative attempt, we refer to the “Taxation and Inequalities” project as performed by the European Association of Tax Law Professors as summarized by the eminent professor Rita de la Feria:

Based on this, what’s ‘Fair’ in a Tax sense is highly dependend when, where and in which socio-economic capacity of someone gets to decide. For the remainderof this paper, we will assume that the applicable Tax Law itself is accepted to be ‘Fair’, or at least the outcome of a democratic process that results in the implementation of a reasonably average consensus of Tax Fairness.

So, to speak in Rolf’s example, for a Fair Tax Label, we test whether a company applies the law and has a ‘Fair’ attitude towards its tax obligations, meaning it should be reasonably cooperative and not overly aggressive. So: how do we test that?

Setting the Scene: Tax Avoidance vs. Tax Evasion

The conversation about Fairness in Tax Attitutes requires a proper delineation between tax avoidance and tax evasion. The definitions of these are mutually exclusive: tax avoidance is choosing a less costly path out of several available options, while tax evasion is falsely presenting path in order to duck taxes in fact owed. The former is legal and revolves around well-informed design and choices, while the latter is illegal and mainly revolves around lying about the facts or obscuring them. Also know as fraud.

Despite the mutual exclusivity when taken narrowly, we’d argue that a Venn Diagram can be drawn where the two overlap still. Somewhere, there exist tax policies that fall under the definitions of avoidance [i.e.: the cost-saving path is actually walked] yet can be considered so artifical or opportunistic that despite falling within the grammatical bounds of the laws, they fall outside the bounds of underlying norms and ethics. Therefore they cross over into an area that we may call ‘unfair tax avoidance’ or ‘unillegal tax evasion’. This will mainly involve applying legislation in contempt of its purported goals and/or constructing artifical paths.

In order to pinpoint where *that* area lies, we mjst dive deeper into some universal tax principles. Like: how could we tell what any law’s purported goal or spirit is, and when a path is forged artificially?

First: The Classical “Functions” of Tax Law

The reason that any possibilities of tax avoidance exist at all, is because of natural tensions between the delineated classical ‘functions’ of tax law. These are:

- Budgetary Function: Taxes are used to raise the budget for public programs and goals.

- Redistributive Function: Taxes are used to influence the distribution of income and wealth.

- Instrumental Function: Taxes are used to steer behavior and address market failures and imbalances.

The Ottawa Taxation Framework, which was developed under the guidance of the OECD during a Ministerial Conference in Ottawa in 1998, carries international consensus that tax laws, in their pursuit of the aforementioned functions, should adhere to the following principles – which have trade-offs:

- Neutrality: Tax legislation should aim to be neutral and fair between different comparable activities so that business decisions are driven by economic rather than tax considerations. Taxpayers in similar situations carrying out similar transactions should be subject to similar tax obligations.

- Efficiency: Compliance costs for taxpayers and administrative costs for tax authorities should be minimized as far as possible.

- Certainty and Simplicity: Tax rules should be clear and easy to understand so that taxpayers can anticipate the tax consequences of a transaction in advance, including when, where, and how the tax will be levied.

- Effectiveness and Fairness: Taxation should result in the right amount at the right time. Opportunities for tax avoidance and evasion should be minimized while anti-abuse measures should be proportionate to the risk they address.

- Flexibility: Tax systems should be flexible and dynamic to keep pace with technological and commercial developments.

How Do these Principles Give Rise to the Possibility of Tax Avoidance ?

Tax avoidance can only exist when there are routes that are less tax-costly than others. After all, tax avoidance is inherently a relative concept. That is, there is only tax avoidance if a more costly fiscal route with the same end situation is conceivable.

When a tax is never levied on a certain behavior, there is no tax to be avoided. When a tax is always levied on a behavior, on the other hand, said tax can only be avoided by avoiding said behavior. In this case, the underlying situation has been realistically altered [i.e.: the behavior does not take place] and by not engaging in the behavior, one falls back to the situation where the tax is not levied (and thus cannot be avoided). Only a tax that is levied sometimes [e.g.: deppending on who engages in the behavior or when the behavior takes place] can be avoided without meaningfully altering the underlying behavior. For instance, in this case, by arguing one belongs to a certain group or by arguing the timing of the behavior.

When such situations exist, this is often a result of tax “instrumentalism”; the legislator may want to encourage or discourage certain groups or timings, and has chosen the tax path to do so. An example here could be a grace period in municipal taxes for newly started businesses. If a grace rule exists where businesses that are less than 3 years old can request too have their municipal tax bill pardonned -a rule which the municipality may adopt to encourage local new firm creation- questions may arise whether less than 3 year old branches or subsidiaries of a pre-existing business qualifies and if so, whether it should argue its case. On the one hand, one may say the new branch adds to the local economy and vibrancy still, and the grace rule may be part of the business case and is effective in its setup. At the same time, however, one may say the rule was obviously meant to help young businesses in the cash critical early phase, and that a local branch of an expanded business does not belong to the target audience…

In addition to situations where one my wonder about the fairness of invoking a measure, there may also be cases where it is difficult to discern whether any path or behavior was meaningfully impacted. For example: there could be a situation where a bottle of grape juice is subject to a lower VAT rate than a bottle of wine. In cases where anyone purchases grape juice, then, one may wonder whether any wine-VAT was avoided, when the underlying path is meaningfully different [i.e.: no wine was bought]. Similarly, a company that applies the Dutch Innovation Box pays less corporate tax than a company with the same profit level that does not. But before a company can apply said Innovation Box, it must -for example- do qualifying and employed R&D work in the Netherlands. If such is the case, the question arises whether any tax was avoided through the R&D. In both cases, we argue ‘no’. In other words:

The More Expensive Path is not Always the Proper Benchmark.

The mere fact that a more expensive path is conceivable, does not make said path the proper benchmark for establishing whether any tax has was avoided at all. After all, it is often possible to deliberately construct a more expensive [and potentiall irrational] path to any end situation, and that does not make all other, perhaps less cumbersome routes, paths of relative avoidance.

The European Court of Justice’ [ECJ] case law supports such a view. For instance: in examining whether a national rule grants a selective and possibly discriminatory advantage, the ECJ must also first establish whether any ‘advantage’ is granted at all, and this too requires a proper benchmark first. In the case of Fiat Chrysler Finance Europe v. Commission (C-885/19 P and C-898/19 P), the Commission emphasizes that the ‘normal’ tax regime [including its beneficial rules] serves as the basis for this:

“[68] To qualify a national tax measure as ‘selective’, the Commission must first establish what the reference system is – that is, what the ‘normal’ tax regime is in the Member State concerned – and then demonstrate that the tax measure in question deviates from this reference system by introducing a difference in treatment between market participants who are in a comparable factual and legal situation in light of the objective pursued by this reference system […] [69] In this regard, it should be recalled that the determination of the reference framework is of great importance in tax measures, as the existence of an economic advantage […] can only be established in relation to a ‘normal’ tax.”

So: what is a ‘normal’ tax? In the Netherlands, according to the Supreme Court and the legislator, the so-called ‘Multiple Paths Doctrine’ applies: when a taxpayer can choose between several paths to achieve the same end setup, they are free to choose the most fiscally advantageous route. This freedom is limited when “the chosen route is selected with no other purpose than to circumvent the intended provision, contrary to what the legislator intended when creating this provision.” [BNB 1994/87].

The well-known Dutch tax ethicist Richard Happé succinctly summarized a series of sources in his paper ‘Tax Ethics, a Matter of Fair Share’ as follows:

“The court has long accepted that the taxpayer is free to choose the most fiscally advantageous route [BNB 1994/87]. The legislator has also expressed this view. During the parliamentary debate on the provisions regarding proper taxation [Articles 31 to 36 AWR], the legislator repeatedly argued that it was not intended to prevent the normal use of permissible means to avoid tax [Parliamentary Papers II, 1955/56, 4080, no. 5. P. 11]. The legal limitation of pursuing self-interest plays a particular role in the doctrine of fraus legis [abuse of law]. This limit comes into view when, according to the Supreme Court, there is a personal motive to evade taxation and the fiscal construction is at odds with the purpose and intent of the law [BNB 1996/4].”

An Informed and ‘Smart’ Tax Path should be the Benchmark:

In summary, the ‘benchmark’ against which any potential savings are identified is a ‘normal’ situation, where the taxpayer has chosen the most advantageous route from several organic options, however one without purely fiscally motivated evasion steps. The benchmark is therefore not the taxpayer who commits fraus legis, nor the taxpayer who chooses a detour to end up in an unnecessarily tax-costly situation, but rather the well-informed taxpayer who uses due dilligence.

Since every Dutch citizen is presumed to know the tax law, this benchmark also includes knowledge of organically accessible regimes. In the Innovation Box example, there would thus be no ‘avoidance’ if a qualifying taxpayer applies the Innovation Box, because non-invoking it despite applying for it should not be considered ‘normal’ as it isn’s the most favorable path of all organically available ones.

In the Innovation Box scenario, one may cosider corporate income tax to be avoided where the company hires persons who were freelancers first, and does so for tax reasons. Again, the path is realistically altered, but it that may now be due to tax reasons. The question arises, then, whether this ‘avoidance’ is objectionable or rather a sign of effective instrumentalism. After all: the Innovation Box has, by proxy, utlimately contributed to more R&D employment in the Netherlands…

When is ‘Avoidance’ [Vis á Vis the Smart Path] Objectionable?

This question can be answered in two ways: through a technical approach or a more intuitive one.

On a tax-technical level, there are already guidelines. The doctrines of Proper Taxation and Fraus Legis (abuse of law), which put limits on the Multiple Paths Doctrine, dictate that a grammatically possible path is to be ignored (proper taxation) or substituted for a more natural path [abuse of law] to determine the due taxes, if the choesn path’s decisive purpose was to avoid taxation when said avoidance is notably contrary to the purpose and intent of the law, and when are no other legal methods to resolve the legal/tax ‘shortcoming’.

In other words: the grammatical interpretation of the law goes first, and a path thaat fits the wording of a provision should be considered legitimate as a starting point and reconsidered only if it is unnatural in it setup and unintended in its outcome.

On a more intuitive level, the test of whether any Tax Attitude is “fair” looks as the setup from 30,000ft and takes a more holistic approach. Factors that may affect the judgment are [1] government efficiency, [2] government attitude, [3] the allround ‘niceness’ of the involved company and [4] scope and intent of the involved provision, [4] clarity of the legal provision, [5] well-known-ness of any loophole and [6] the nature and personal biases of the person passing jdugment. And this intuïtive test is much more subjective and should, for that reason alone, not take priority over the more technical one. After all, presented with a situation where certain avoidance fits the law but does not fit the juror’s morality, they should “protest, go to court or into politics, or migrate to a different country” rather than determine that the involved taxpayer is in the wrond.

Does this mean that every avoidance opportunity that is apparently part of the ‘Smart Path’ and that remains unaffected affected by the Proper Taxation or Abuse of Law docrtines is ethically pure and therefore “Fair”? No!

Limits to ‘Legalism’ and the Teacher Who Wants to Make a Peanut Butter Sandwich. About Malicious Compliance.

A notion where a mere grammatical interpretation of the law suffices to test Fairness too narrow a view of citizenship. Yes, the citizen should -first and foremost- trust that the grammatical provision of the law is the most accurate representation that a competent legislator could draft as the outcome of a democratically legitimate process. To put that into modern management speak: it should be assumed that Fairness was already part of the ‘head’ of the legislative process, and should not be added at the tail. After all, if we were to assume that the law should not in principle be applied as it was written up, this would lead to a democratic deficit arises as anyone applying it should also be their own juror as to whether the provision actually applies as stated, and this can lead to inefficiencies and even to dangerous situations.

But: it is illusory to think that words can capture all scenarios, and there is also such a thing as ‘malicious compliance’. Within the social contract of a well-functioning democratic order, it is therefore also up to the citizen to apply the law to its reasonable meaning and, for example, not to feign paths to fit within a grammatical norm or description without taking the meaningful actions that make up said path.

In primary school, children learn to explain clearly and use language efficiently by writing instructions for the teacher on how to make a peanut butter sandwich. This requires a step-by-step manual because the teacher is, of course, intent on being ‘maliciously compliant’. If the young student writes ‘take the bread, open the jar, put the knife in the jar and ensure that about half a centimeter thick peanut butter is on the length of the knife blade, take the knife out of the jar and spread the peanut butter on the bread’, the process inevitably ends with a smear of peanut butter along the length of the bread bag since it was not stated anywhere that the bread should also be taken out of the bag first.

Neither law nor case law explicitly states that there is any hierarchy between the methods of interpreting a law, although it is generally assumed that the grammatical meaning carries particular weight and that legal interpretation should logically not lead to an application of the law as expressly not formulated by the legislator [BNB 1996/138]. Translated to the peanut butter test, this means that it is generally assumed that logic helps dictate how to make a sandwich, and that the grammatical text of the instruction is included in that logic.

Those who engage in malicious compliance and apply the law only grammatically invite great inefficiencies and deserve a government that is equally restrictive. For elements such as a hardship clause, which is in a sense the soothing counterpart of proper taxation and fraus legis, there would be no place then…

Limits to Teleology

At the same time, no ‘thinking along’ should ever be required to a degree whether the taxpayer is expected to apply provisions against their wording, and any legislator also cannot cut corners in the wording process on account of expectig the taxpayer to be overly aware of their true intentions. In other words: the legislators’ intent must be sufficiently clear from the wording of the provision, which should always be the starting point. And to prevent laws from losing their force, their wording must be sufficiently clear to be binding but sufficiently open to apply dynamically.

Coming up with such wording is very complicated, and no one can succeed linguistically perfectly without fail. When the wording of a law therefore leaves room for an apparently unintended tax savings that do not result from tax-driven and artificial detours, it would be overly simple in turn to attribute the unwanted outcome to unfair motives on the taxpayer’s part.

Reflecting on the Ottawa Framework: often, a law that provides an unintended but unfraudulent opening for potentially unintended tax avoidance, does not properly incorporate the Ottawa Framework’s Five Principles. For example, if there is an opportunity for avoidance in two situations with no relevant differences, the law is probably not neutral, not efficient, not certain and simple, not effective and fair, or not flexible. And if the law does meet those criteria but the savings opportunity is still perceived as unjust, the assessor essentially disagrees with the underlying policy.

In short: the legislator has a broad mandate and therefore also a broad responsibility. And when there is an ambiguous savings opportunity for an organic situation, it may be a somewhat high demand to ask citizenship to autonomously refrain from it. That’s why this expectation is already precluded in the benchmark step: the taxpayer is expected to be rational and tax smart and applying the least costly organic route.

At the same time, it is reasonable to ask citizens not to twist themselves into meaningless and/or inorganic contortions with the sole or primary goal of tax savings, and certainly not to feign routes or situations for that purpose. Essentially, determining where a legitimate route change due to intended instrumentalism transitions into a meaningless and malicious fiscal setup is the domain of fiscal ethics.

So: what is Right and what is Wrong?

In a situation where someone agrees with the legislator’s considerations and accepts a tax law in itself, but believes that a taxpayer faces a choice to organize a path that leads to an advantage, the ethical judgment around goding so revolves mainly around the degree of artificiality of the path, the morality of the pursued goal, and, sometimes, the identity of the taxpayer.

For example, the average citizen may find it much less objectionable when a young healthcare worker asks to postpone the official purchase and transfer date of their first home past year-end if a lower Real Estate Transfer Tax is to apply in the new year, than when a multionational group that sources fossil fuels sets up a relatively meaningless group treasury company in a low-tax island jurisdiction where it has no other operations (insofar as that would have any effect).

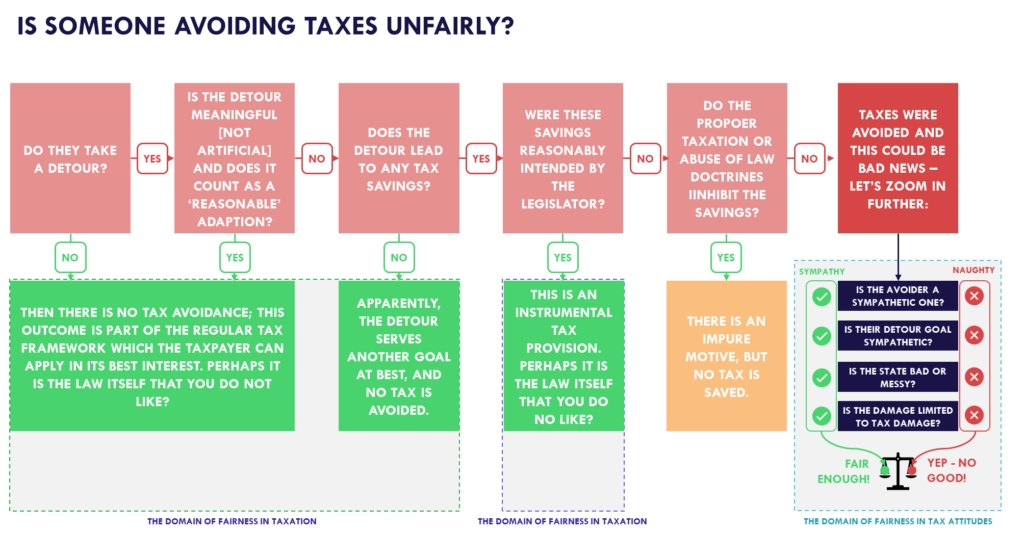

Viewed this way, a fiscal-ethical framework might be flowcharted as follows:

In short: if someone does not take a detour, there can be no avoidance. It requires a conscious act. And if a detour is taken but it is meaningful and belongs to normal adaptations, then there is no avoidance because the ‘regular’ tax burden should be determined based on the path now taken.

However, if the detour is inorganic and leads to a saving, there is tax avoidance. However, if the tax savings were intended, this is due to instrumentalism and the detour was probably intended [i.e.: buying grape juice instead ofwine]. Whether the provision’s goal is “Fair” is not so much a matter of Fairness in Tax Attitudes, but mainly a matter of Fairness in Taxation and policy ethics.

If the advantage was reasonably not intended, the setup can be prevented by the doctrines of Proper Taxation and/or Abuse of Law, if the wording of the provision is ambiguous at least. If these doctrines succeed, however, there is no longer a saving, so no tax is avoided. The attempt may remain unethical, but the avoidance element is thwarted.

If the detour setup for an unintended fiscal advantage is not thwarted based on its artificiality, there is room for a fiscal-ethical judgment. The setup is more morally justifiable if it serves a sympathetic goal of a sympathetic party without causing further harm, and/or if it, for example, avoids tax revenues for a malicious regime.

Viewed this way, many paths labeled as ‘tax avoidance’ actually fall outside that definition. Run the chart with mortgage interest deduction, for retaining earnings, or for buying an emission-free car. If someone disagrees with the outcomes for such cases, they primarily disagree with the legislator’s choices and not so much with the taxpayer’s. And since taxpayers are free to choose the most fiscally advantageous route from several available and real routes, it is not fiscally unfair to use a tax measure the goal or scope of which is contentious to some.

Fiscal ethics actually concern situations where someone manages to artificially realize an unintended advantage and assesses to what extent that is acceptable.

So?

It would be good to see reflected in the public debate, that many tax-saving opportunities are not a matter of the taxpayer’s ethics but of the legislator’s. And if the democratic process is efficient and does not address the perceived deficiency, it must be assumed that the democratic majority upholds a different ethic than the person perceiving the injustice.

At the same time, taxpayers cannot suffice by pointing out that a tax-saving setup has succeeded and is therefore acceptable merely because the democratically adopted law does not thwart it. Unforeseen or linguistically impossible to seal situations absolutely exist where a saving might be achieved yet Fairness in Tax Attitudes dictate that the taxpayer grasp it. However, such situations should be considered rare and should be concluded on lightly, and tax ethics can only be called upon with any force when the domain is clearly delineated.

There is no direct link between budget deficits for education and a founder that retaining earnings rather than taking a taxable dividend straight away, but they are not entirely unrelated either. The extent to which citizens are willing to forgo potentially unintended deferrals or savings or pass on tax-saving detours is significantly related to how Fair and just they perceive State and society to be. And generally, citizens perceive a State or society as more fair when they do not attribute potential shortcomings in the law to the morality of its citizens, and does not assume that all that is more expensive is purer. Within this, it is up to taxpayers themselves to ensure that society’s view does not sour. You can be smart about your taxes, but you cannnot lie and contort.

What are the Implications for a Fair Tax Label?

For a Fair Tax Label, we shall refrain from any judgment on Fairness in Taxation: the legislator, as the spearhead of any efficient democratic process, should be trusted to build Fair and accurately worded laws. In order to test whether any taxpayer’s Tax Attitude is fair, however, we shall test for specific outings of cooperation:

- Tax Compliance: timeliness and completeness of statutory and tax filings, UBO transparency and residency, and Tax Authority Disputes;

- Effective Tax Rate: does the companny or group pay a ‘realistic profit tax’ as compared to the statutory profit level, and any blacklisted jurisdictions involved with an ETR-mitigating effect?

- Transparency: do the UBOs reside in FATCA/CRS participating jurisdictions and do they properly report and pay their Personal Income Taxes?

- Aggressive Tax Planning: does the group or company meet, without mitigation, any of the OECD’s Hallmarks of Aggressive Tax Planning?

- Tax Driven Structure: is any top holding entity interposed for treaty reasons?

With this test, we can see whether detours are taken and if so, whether they are properly communicated so that mitigating tests may capture them. If any taxpayer is fully transparent and non-aggressive in their routing, they should be considered cooperative taxpayers and good citizends in that regard. We consider that this test takes a broad and safe approach to the flowchart above, and actually stops around the detour question rather than pass judgment on any succesful tax avoiding setup. Any impurities in tax outcomes from there on out, should be a matter of Fairness in Taxation and the government’s, rather than Fairness in Tax Attitudes and on the taxpayer.