The European Commission (“EC”) proposed a Council Directive on “Business in Europe: Framework for Income Taxation” (BEFIT) on 12 September 2023 [link to the EC’s legislative BEFIT-batch here].

The goal of the Directive is to determine an EU-wide ‘consolidated tax base’. Why? Even though there are already some EU Directives on direct taxation, the direct taxes fall under the exclusive competence of the EU Member States, so a plethora of systems remains in place on te single market. The underlying cause or reason is that direct taxes are not harmonized under the Treaty of the Functioning of the EU (“TFEU”); a political choice, mainly caused by the (political) desire of the EU Member States to decie on their own fiscal policies and on how to fund their respective public spending.

So in other words: the ‘fiscal instrument’ is not centralized in the Union and Member States are free to design and tune their own systems, within the bounds of course of certain EU Minimum Standards and Directives. In certain ways, this contradicts the goal of the ‘EU Single Market’ to remove frontiers so that free movement of goods, persons, services and capital are ensured within the EU.

The fact that all 27 EU Member States have their own rules on Direct taxation can in itself already be seen as a trade barrier, making it more difficult and costly to do business across the EU.

The EC as the shepherd of the EU single market has a longstanding desire to implement an EU common corporate income tax base and has therefore launched the BEFIT proposal. The EC believes that BEFIT will enhance to the EU level playing field, while reducing compliance costs and legal uncertainty. This post is to break the ice on BEFIT; it’s workings, the background of the issues it addresses and the reasonings behind the fixes it proposes!

How does the EU internal market work?:

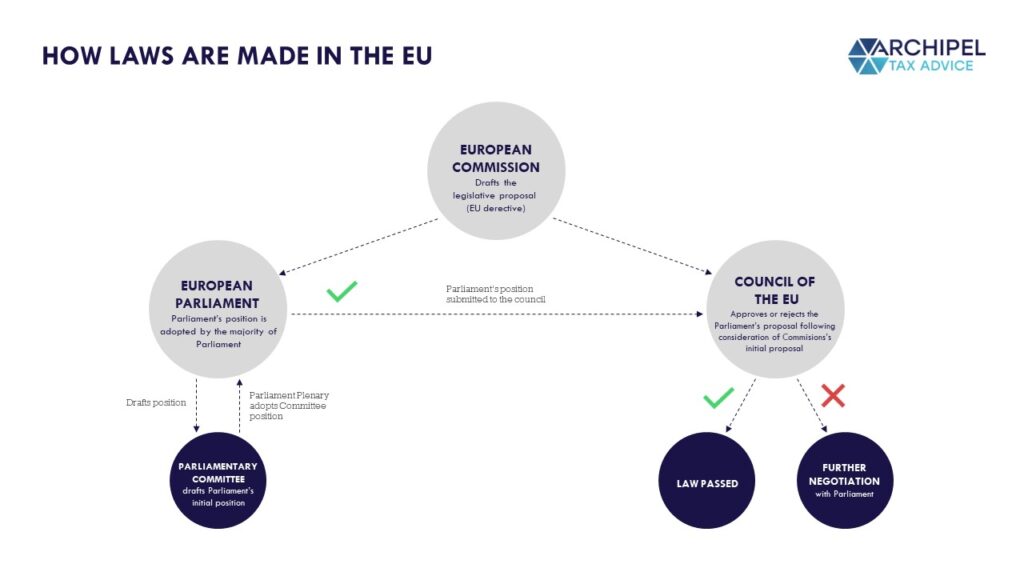

Laws in the EU are made through a legislative process that involves three main institutions: [1] the European Commission, [2] the European Parliament, and [3] the Council of the EU. Here’s a quick overview of the legislative process.

In short: the European Commission has the (very valuable) ‘right of initiative’. So the European Commission submits a proposal to the Council and the European Parliament. The European Parliament examines the proposal and may choose to either adopt it or to make amendments. The Council may then decide to accept the European Parliament’s decision or to amend it [in the latter case, the proposal is returned to sender].

If the Council approves of the proposal, the law is passed as either:

- A regulation, which is binding in its entirety and directly applicable to all member states.

- A directive, which is binding, for all or some member states – in terms of the results to be achieved – but member states are free to pick the form and methods to implement the directive.

- A decision, which is binding in its entirety for those to whom it is addressed.

If you want to read more about how the institutions of the EU work and why the European Commission is the one proposing these measures – check out this blog post:

What bottlenecks are caused by existence of multiple tax systems within that Single Market?

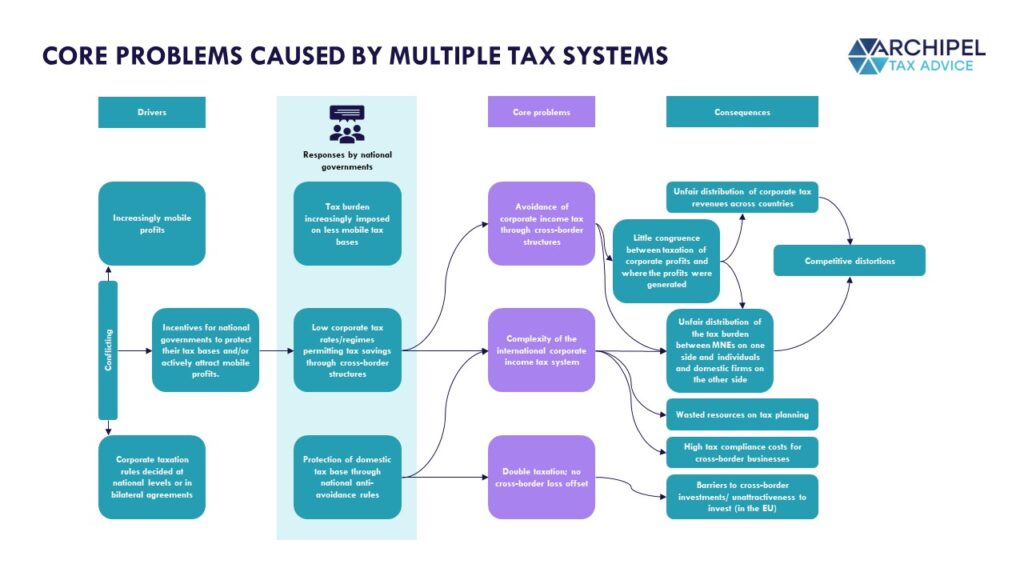

The EU remains a unique Union of sovereign states, within which competition and market access conditions are nonetheless intended to be streamlined. Yet, certain decisions and systematics are left ‘within the autonomy’ of the respective Member States. Such as tax systems. And as conditions between States can be vastly different, it is only logival that their Tax Systems can be as well. On a ‘Single Market’, this can lead to an intricate web of consequences that don’t align with the Single Market ideals.

For instance: currently, multinationals are faced with 27 different tax systems to be compliant with in the EU, making it difficult and costly for them to do business. This complexity creates an unlevel playing field and increases tax uncertainty, and as a result tax compliance costs for businesses operating in multiple EU member states. It also puts EU businesses at a competitive disadvantage compared to businesses operating in markets of comparable size elsewhere.

The complexity created by the multitude of tax systems in the EU is displayed in more detail in the visual below:

The ‘making of BEFIT’ timeline:

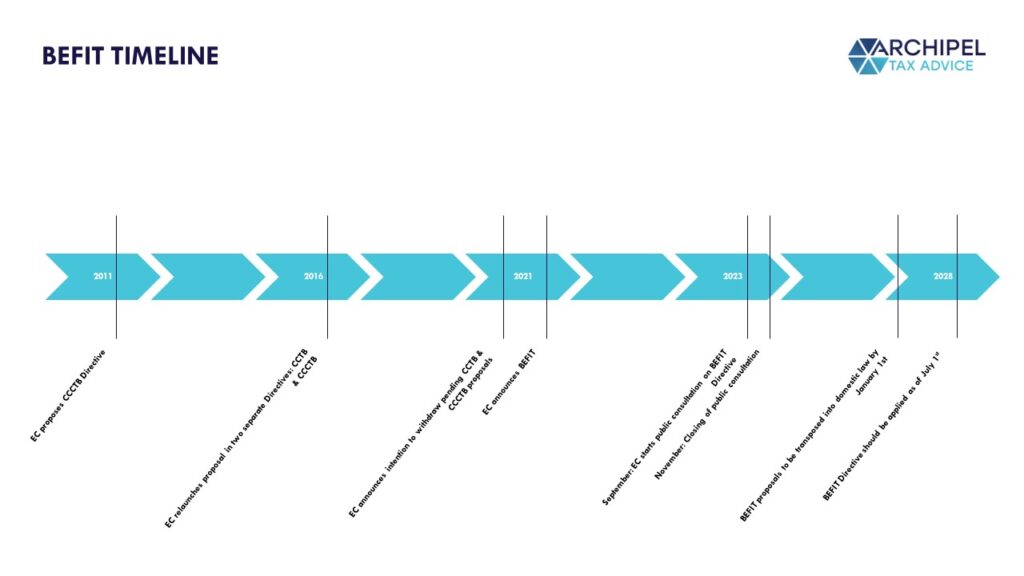

In order to address this ‘inefficiency’, the EC has dusted off its longstanding desire to implement a consolidated EU tax base. We say longstanding, because previous initiatives have failed. We revisit:

- Already in 2011 the EC proposed a directive for a common consolidated corporate tax base (“CCCTB”).

- In 2016, the EC relaunched the proposal but in two separate Directives, (i) the common corporate tax base (“CCTB Directive”) and (ii) the CCCTB. The intention was that the EU Member States would be more willing to accept a common corporate tax base without the consolidation, so that autonomy would still be ensured and that extra “C” could be added later in the process.

- In 2021, the EC announced an intention to withdraw the pending CCTB and CCCTB proposals.

- In 2021, the EC instead announced BEFIT as part of its communication on Business Taxation for the 21st Century.

- During September 2023, the EC started a public consultation on the BEFIT Directive.

- 15 November 2023 à closing of public consultation.

- The BEFIT Directive is to be discussed and approved by the European Parliament and the Council of the EU (refer to paragraph 1). Voting

- EU Member States should transpose the BEFIT proposal into domestic law by January 1, 2028.

- The BEFIT Directive should apply as of July 1, 2028.

How does the BEFIT proposal work?

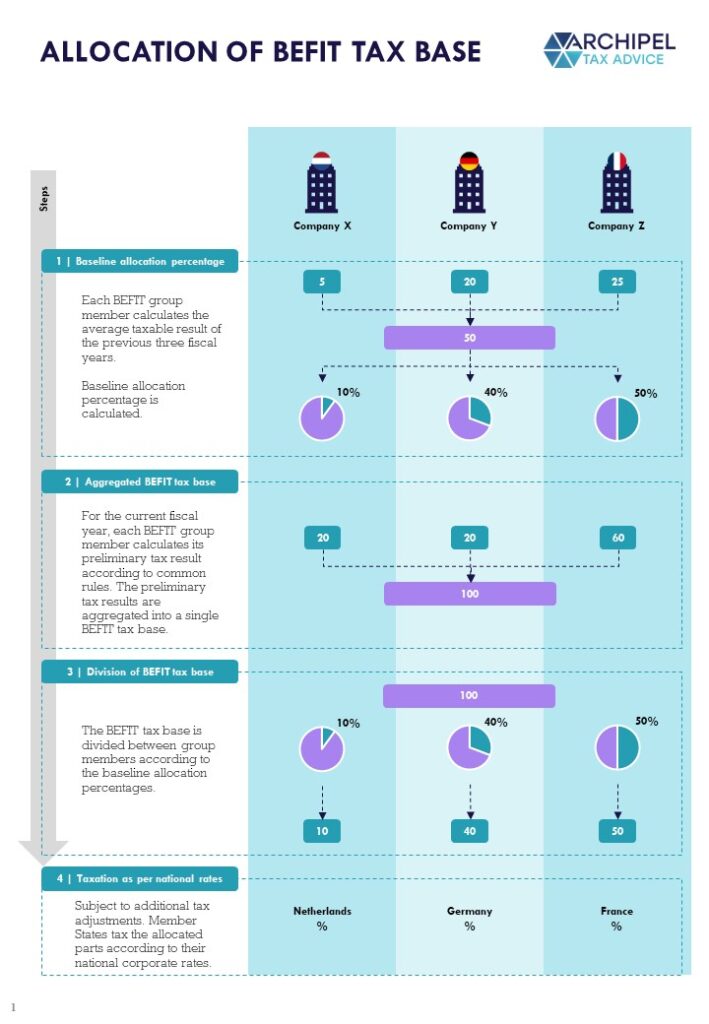

The BEFIT Directive sets out a framework of tax rules to help companies in scope to determine their tax base. A ‘one-stop-shop’ will allow these businesses to file an information return with the tax bases of all its EU subsidiaries with the tax administration of a single EU member state.

Those tax bases will then be consolidated at the EU group level and allocated to each subsidiary in the group. Finally, member states will apply their own adjustments and corporate income tax rate to the allocated tax base of the local subsidiary.

Who is in scope?

BEFIT applies to groups with a consolidated revenue of EUR 750 million or more.

BEFIT Technique: the ‘Permanent Allocation Method’

The ultimate goal of the Directive is to define a permanent allocation method. This is a formulary allocation method on which basis profits are allocated to group members in EU Member States. Considering that first a debate will be needed to determine how exactly profits are to be allocated, this method is scheduled to apply per June 30, 2035. The bigger EU markets are expected to argue that market synergies, employees, clients, factories, stores etc. should play an important role, while smaller economies typically tent to lean more towards intellectual properties, head office functions, etc.

Step 1 – Calculation of the preliminary tax result and allocation %

The EC therefore proposes a transitional mechanism on which basis the results are allocated to group members based on the average preliminary taxable results in the prior three fiscal years. In this step, the preliminary individual corporate tax base is determined by making adjustments to the results in the financial accounting statements (exemptions, non-deductible items, depreciation rules, etc).

The allocation percentage is the based on the following formula:

Step 2 – Determine BEFIT tax base

For the current fiscal year, each BEFIT group member calculates its preliminary tax result according to the BEFIT rules. The preliminary tax results are aggregated into a single BEFIT tax base. The staring point are the financial statements of each group entity that are based on the accounting standard of the ultimate parent entity (or the filing entity if the ultimate parent is not in the EU).

The BEFIT group can set-off cross-border tax losses.

Step 3 – allocation

The BEFIT tax base is divided between group members according to the baseline allocation percentages.

Step 4 – Local adjustments

Subject to national corporate income tax rules, local adjustment can be made. This could for example be tax incentives, further deductions, Pillar 2 GloBE adjustments, etc.

Want to Discuss? Book a Slot, it’s on the House!

Your pick – whose face do you like better for the topic?