If you’ve landed on this post, chances are you’re considering a business valuation. Perhaps because you want to buy or sell a company, or because you’re not planning an ‘external’ transaction (with a third party) but rather an ‘internal’ one (e.g. with employees) with its own tax implications. And soon enough, vague terms start coming your way: Fair Market Value (FMV), Enterprise Discounted Cash Flow method (DCF), Advance Tax Ruling (ATR). Does it really have to be that complicated? You’re already immersed in the economy, and there’s an old Dutch saying: “those who come from the market know the price.”

For my original article in Dutch; follow this link.

And it’s true: the market ultimately determines the price. In a classic market with perfect competition, the seller wants to sell for as high a price as possible, and the buyer wants to buy as low as possible. The price they agree upon within this tension is the apparent price of the good — in other words, the FMV. In Dutch we call this the ‘waarde in het economische verkeer’ (WEV).

In this case, that FMV results from business considerations rather than tax considerations. Yet, FMV plays a leading role in taxation. After all, most taxes are percentage-based and levied on an underlying (commercial) transaction. The tax burden is thus directly linked to the agreed transaction price. And this is where the fiscal tension comes into play, as we discuss in this article: because when the tax burden is tied to the transaction price, you can influence the tax burden by influencing the transaction price.

Between independent parties, it’s almost impossible that a tax motive to agree on a low price would outweigh business considerations. It’s hardly conceivable that someone would be willing to accept an operational loss just to reduce transaction tax. But when the transaction takes place between “related parties” (for example, between family members or companies with common shareholders), that non-commercial — read: tax-driven — motive can indeed be a reason to agree on a different transaction price than one might set on the open market. And that’s when things get fiscally complex…

To determine that FMV, tax law essentially pretends that the related parties are negotiating with each other as if they were independent — at arm’s length. So, what if the seller indeed wanted to secure the highest possible price and the buyer the lowest possible price? In short: what if these parties weren’t related? How much tax would then be due?

In this article, we zoom in specifically on the tax rules — let’s call them the “hypothetical parameters” — that apply to this scenario. Specifically, those that apply when non-marketable business shares change hands. That is, shares that are not publicly traded and therefore do not have a current market price. For those interested!

1. First of all: why would anyone care about the price you use when you’re not actually selling your company?

Because the tax implications of any share transfer are directly linked to its ‘value’. And as mentioned, this becomes particularly interesting when we’re talking about transactions within related parties. In such cases, you can make arrangements specifically to minimize tax. Think of it this way:

Example 1: Dad gives shares to his son.

The father’s business is doing well, and the shares yield a significant dividend. Dad gives his son shares in the company. This could qualify as a gift: for example, if the son receives the shares for free or for a price below their fair market value. In that case, gift tax would be based on the difference between what the son pays and what the shares are worth. So, what are the shares worth?

Tax Breakdown: Under the inheritance and gift tax law, a taxable gift occurs if (i) the father is financially diminished, (ii) the son is enriched, and (iii) there is intent and awareness to benefit the son. In a parent-child situation, this intent of generosity is usually assumed. However, this does not apply if the son provides a counter-performance.

Suppose the transferred shares are worth €1 million, but the son only pays €10,000; then the son is (in principle) liable for gift tax on the remaining €990,000, resulting in €185,000 in gift tax due, without accounting for any exemptions. It makes sense: the son could immediately sell the shares at their “FMV,” resulting in a cash gain of €990,000 from this share transfer. If the father had simply gifted €990,000 in cash, there would never have been any ambiguity regarding the gift’s scope and thus the tax liability.

If these shares also represent a “substantial interest” (>5%) for the father, he would additionally owe a 33% (2024 top rate) substantial interest tax in Box 2 on the €1 million value minus his acquisition price for the shares. The acquisition price generally does not increase by the gift tax paid.[i] The short answer to who cares about the value used here is simple: the Tax Authorities.

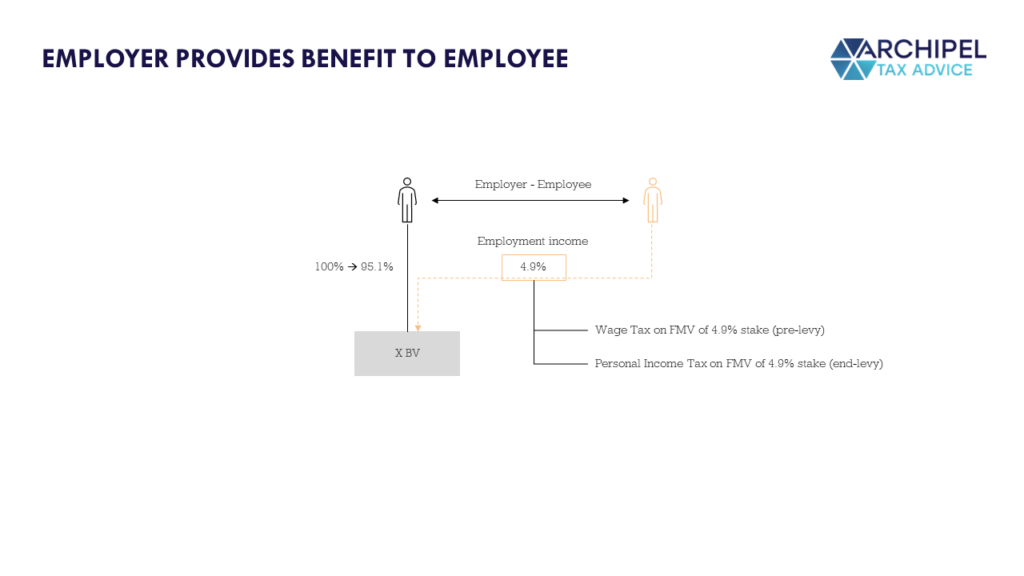

Example 2: Employer Grants Shares to Employee

Another example: an employer grants free shares to several employees to reward good work and retain them for the future. In theory, this could also qualify as the employer’s generosity (and thus fall under gift tax), but it is more likely that the allocation originates from the employment relationship, making the stock grant taxable as wage since it is a “benefit derived from employment.”

If employee X receives shares worth €10,000 for €0, a maximum of 55% wage tax is due on that difference (the benefit).[ii] After all, the employee could theoretically immediately liquidate the shares for their “FMV” of — evidently — €10,000. If the employer had simply paid out €10,000 in cash, there would have been no ambiguity about the wage benefit and its amount. If the shares granted are meant as a net benefit for the employee, grossing-up must be applied to determine the wage tax burden, meaning the employer must then pay an additional amount of wage tax of [€10,000 / [1 – 0.55]] – €10,000 to the Tax Authority.

In short: the Tax Authorities certainly have a stake in this.

In both cases, a lower valuation results in a lower tax burden, so both the father and the employer may be inclined to see their business in a more pessimistic light — likely more pessimistic than they would if they were actually selling the business. This gives the Tax Authority grounds for suspicion: is there tax evasion at play?

That said, a reverse motive is also possible. After all, if it’s about a deductible gift-in-kind, a lower valuation would result in less deduction and thus a higher tax burden. In this case, there might be a tendency to set an “unrealistically high” valuation. So, it sounds like there’s a mythical range where that valuation is fiscally “just right”? Exactly!

2. At what level should I set the price for determining my tax liability? At what they’re worth…

In short: at their FMV. This applies to both income tax[iii] and gift and inheritance tax[iv] as well as corporate tax.[v] But what exactly is that? The term FMV has a clear meaning in everyday language but is also, in tax terms, a kind of compressed file containing a whole series of underlying tax theories. For example, the Supreme Court[vi] defined FMV as:

> “the price that would be paid by the highest bidder when the item is offered for sale in the most suitable way after the best preparation.”

— Supreme Court, February 5, 1969

According to the parliamentary proceedings of the first instance where FMV was mentioned in a law, it should be “interpreted within the framework of the specific legal provision,”[vii] implying that it may be defined differently per law. The Supreme Court paraphrases this viewpoint, stating that it should not be assumed “that this term [FMV] in the provision in question necessarily has the same meaning as in other laws.”[viii] However, in practice, this nuanced interpretative difference does not yet seem to emerge in the valuation of non-marketable shares, if we look at FMV across the Wage Tax Act 1964, Income Tax Act 2001, Corporate Income Tax Act 1969, and Inheritance Tax Act 1956. To our knowledge, this nuance has never been raised or substantiated in practice.

In summary: for tax liability, you use “the” FMV — which is, in principle, the same across the tax system. So, in the examples above, father, son, employer, and employee all use the same FMV to determine their tax obligations. But:

3. Is value something different from price?

Yes. And it’s worth first pausing to consider the difference between price and value, and how tax law blurs this line.

An illustrative example is a garage located in the Concertgebouw neighborhood in Amsterdam, which was listed for sale in 2020 for €995,000. On August 31, 2021, the owner — perhaps on the advice of the listing agent — lowered the asking price to €690,000.[ix] As of this writing, it remains to be seen whether a willing buyer can be found to pay that amount for 22 m². The price per square meter would still be over €30,000. But: “you only need one person crazy enough.”

If a billionaire had bought the garage for €995,000 last year and gifted it to his daughter a month later, €995,000 would be considered the FMV for gift tax purposes. However, this isn’t the “actual” value of the garage if no other “crazy” buyer would ever come along again, meaning the box could never be sold for that sum again. Yet, for tax purposes, that original, unusual transaction would form the most relevant reference point to establish the FMV at the time of the billionaire’s gift to his daughter (see also category 4.1 below), as the price paid in an independent transaction is decisive for tax purposes. As a taxpayer, you’d need a very strong argument to advocate for a lower FMV in the closely following non-independent transaction. The reverse scenario is also quite plausible: if significant time passes between transactions and relevant changes occur (e.g., the real estate market collapses), or if the owner of a neighboring garage purchased it for €150,000 and then gifts it, the external purchase price wouldn’t necessarily represent the “value” of the garage.

4. So how do you determine what such a share is worth on the open market?

Here, we distinguish two “temporal” categories: (1) assets where you can derive the value from a relevant “reference valuation” (that is, a recent, comparable yet independent transaction), and (2) assets where you cannot, due to the absence of a reference transaction.

4.1 When a reference transaction occurred recently or afterward:

The Inherited Chinese Vase

If, just before the taxable moment in the two examples above, an independent party bought shares, you could derive the FMV — for your own tax position — from that transaction. Even if that transaction occurs *after* the share allocation or gift, it can still be relevant for the prior valuation, as the Supreme Court considered in the “Chinese Vase” ruling.[x] This well-known case involved heirs who found a Chinese vase in the attic, dusted it off, and estimated its value at €50. Over the years, in an almost comical turn of events, the vase’s value kept rising until it was eventually — to the heirs’ surprise — auctioned at Sotheby’s for tens of millions.

The maximum period that may elapse before a reference transaction loses relevance is not precisely defined, though certain real estate case law suggests that periods longer than around 2.5 years exceed that limit.[xi] However, this period can likely be extended if it can be demonstrated that all other factors (market conditions, state of the object, etc.) have remained mostly unchanged.

The Gifted Painting

On the other hand, recent art-related case law has extended this reference period to as much as 13 years! On July 10, 2021, the Arnhem-Leeuwarden Court of Appeal ruled[xii] in a case regarding the FMV of a painting donated by individuals (including in 2014) to the Rijksmuseum, which qualifies as a “cultural institution-ANBI.”[xiii] Donations made to an ANBI reduce the donor’s income tax base to a minimum of zero.[xiv] The amount of the deduction for a gift-in-kind is the FMV.[xv] Naturally, it is in the financial interest of the donor (who also has other Box 1 income) if the FMV of the painting at the time of donation is as high as possible.[xvi] An appraisal, commissioned by the Rijksmuseum, valued it at €9,000,000, taking into account the Art Market Research index and prices of comparable paintings.

The Tax Authority found this value too high, pointing out that the 1991 auction price was €2,495,590, which would be worth only €4,049,002 today when adjusted for inflation. That amount also aligns more closely with the 2010 valuation used when the family trusts were dissolved. In the appeal, the Tax Authority revised its position to €7,500,000 based on its own appraisal.

However, the Court sided with the taxpayer, determining that the FMV of €9,000,000 was substantiated, particularly given a very similar painting sold at auction in 2001 for approximately €10,000,000. The Court even noted that the 2001 price would have been around €14,000,000 if adjusted to today, hinting that the taxpayer might have achieved a higher valuation. What’s notable is the Court’s reliance on the auction price of a comparable painting from 13 years earlier. Although the Court’s reasoning may not be entirely logical, the outcome is defensible considering the valuation report.

Software Developer’s Stock Participation Plan: The Impact of a Later Third-Party Transaction

In a recent ruling by the North Holland District Court (December 23, 2021, nr. HAA 17/3466), the issue was the share value for wage tax purposes on August 21, 2013. The court determined, “in good justice,” the FMV based on a later reference transaction dated April 10, 2014, due to a lack of solid price substantiation from both the Tax Authority and the taxpayer.

The reference date was the Transfer date, but the Letter of Intent (dated November 15, 2013) already stated the value used. The court disregarded the Settlement Agreement with the Tax Authority dated August 5, 2013, which had set the FMV for tax purposes at €1,626,840. This extends the Chinese Vase precedent from inheritance tax to the wage tax domain. For clarity: €1,626,840 was the agreed-upon value of the entire share capital in the shareholder of the employer company, which was a software developer for the oil and gas industry. Employees would participate in the capital of that shareholder through a Staff Participation BV, suggesting that the “business” price for the 10% stake held by Staff Participation BV in the shareholder was €162,684.

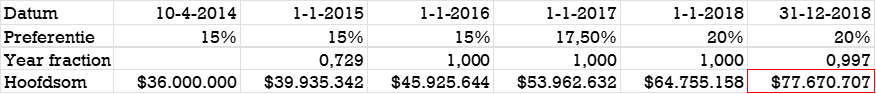

The April 10, 2014 reference transaction (8 months later) involved the purchase — for $36,000,000! — of another share class, convertible cum-preferred shares, which represented 20% of the total share capital of the employer’s shareholder. The court noted that you can’t simply calculate 36 / 20% = $180,000,000 as the total company value, because the convertible cum-preferred shares do not grant rights to residual profits but instead to a 15%-20% preferred dividend. In other words, ordinary shares and cum-preferred shares often do not have the same FMV. In this case, the court concluded that the convertible cum-preferred shares were worth more than the ordinary shares. This is supported by a later 2018 sale where the 80% ordinary shareholders received $40,000,000 and the 20% preferred shareholder received $83,000,000. It’s a reasonable conclusion, but certainly interesting. It seems the maximum principal (including compound accrual) of the cum-preferred shares was $78,000,000 at the end of 2018 if dividends on the cum-preferred shares had never been paid. How this reached $83,000,000 is not entirely clear, especially as payment was apparently made in USD in 2018. See the maximum accrual below.

Another question we have is to what extent that 83:40 ratio in 2018 says anything about the value ratio between the cum-preferred and ordinary shares in 2013. After all, the 2018 sale price was unknown at the time. If the 2018 buyer had paid $180,000,000 instead of $123,000,000 — allocating approximately $97,000,000 to the ordinary shareholders — this substantiation would have skewed the other way. The taxpayer also believed that the ordinary shares were worth less (or even worthless, see para. 30) than the convertible cum-preferred shares, which the court supported.

Additionally (though the court does not mention this), it’s reasonable to conclude that the convertible cum-preferred shares were worth more than the ordinary shares if that conversion results in ordinary shares at no cost. Based on this, the court concluded that the total shareholder value had to lie somewhere between $36,000,000 and $180,000,000 and thus took the exact midpoint: $108,000,000. This amount was discounted by 15% (the initial preference) from April 2014 back to August 2013, resulting in $99,000,000, then a 45% discount was applied ($54,000,000) to account for the explosive growth the company was experiencing. In other words: merely discounting by 15% underestimates the company’s rapid potential value increase. Going back in time, a substantial reduction in value was appropriate, which was arbitrarily set at 45%. According to paras. 92-93, this valuation also accounts for the 5-year transfer restrictions on the employee participations and the lack of voting rights, although it is not explicitly stated that these factors are embedded in the 45% discount.

In para. 94, the resulting FMV ($54,000,000, or €39,000,000) is fully considered as a benefit to the employees (i.e., 100% of the shareholder value), with €1,626,840 first deducted, and then the remainder multiplied by 10%, representing the Staff Participation BV’s stake. This may be confusing but is effectively the same as if you multiplied €39,000,000 by 10% and then deducted €162,684.

Separately, one would typically expect a final adjustment for lack of voting rights and transfer restrictions, as these do not affect the total shareholder value but only the FMV of the employees’ participations. Applying such discounts at a “higher” level means the absolute size of those discounts is also larger: 25% of 1,000 is more than 25% of 100.

In other words, using the same input variables as the court, we would have seen the calculation as follows:

It’s worth noting that the court is free to establish the FMV “in good justice,” allowing for a certain degree of roughness in the valuation. See the starting FMV of $108,000,000 and the rounding down. For the taxpayer, however, it’s essential to present a mathematically sound argument, as this strengthens the plausibility of their case. As seen in the above table, this rough approach ultimately favored the taxpayers.

Additionally, paragraphs 70-71 of the ruling are interesting, where the court considers that multiple share purchase negotiations with third parties in mid-2013 are relevant to the valuation, despite those negotiations being later abandoned. Naturally, later actual transactions provide a lens of plausibility to the earlier negotiations, but the court also appears to assign independent significance to the negotiations even if those later transactions had not taken place.

With a recent (or not-much-later) third-party transaction, valuation is often easier and theoretically more accurate.

This temporal category is, in principle, the most standard route for valuation. There may be some time between the taxable event and the reference moment, but not enough to entirely negate the reference value’s significance. In such cases, the valuation calculation should weigh the reference value, with other valuation components (see Category 4.2 below) serving as a complementary element in the formula.

If we revisit the FMV definition (“the price that would be paid by the highest bidder when the item is offered for sale in the most suitable way after the best preparation”), it primarily involves two opposing forces:

1. The buyer aims to buy at the lowest price and makes the best preparations; and

2. The seller aims to sell at the highest price and sells to the best bidder.

It’s important to recognize that a 100%-relevant reference sale (i.e., a current sale of the identical asset in entirely unrelated circumstances) conclusively determines the FMV of any asset, as these two forces yield an equally conclusive business outcome (the purchase price). Therefore, valuing readily marketable assets, including shares, is straightforward for tax purposes. This is why FMV, as a corrective valuation measure in tax law, is particularly (or even solely) relevant for related-party transactions.

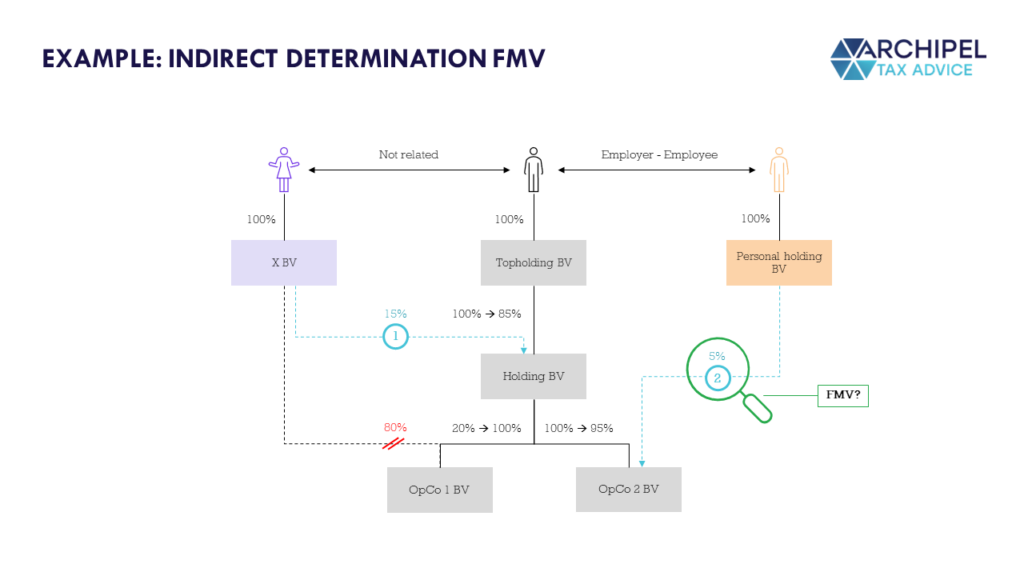

In our view, a reference sale can also have an indirect effect. An illustrative example of this is the following scenario:

In this scenario, X BV holds an 80% stake in OpCo 1 BV. The remaining 20% is owned by Holding BV, which, in turn, is fully owned by Topholding BV. Holding BV also owns all shares in OpCo 2 BV, without any additional assets. X BV wishes to “swap” its 80% stake in OpCo 1 BV for a 15% stake in Holding BV, which will acquire the 80% interest in OpCo 1 BV, resulting in Holding BV owning 100% of OpCo 1 BV (Transaction 1). Subsequently, an employee of OpCo 2 BV, through their personal holding company, will acquire a 5% interest in OpCo 2 BV at no cost (Transaction 2). The Ultimate Beneficial Owner (UBO) of X BV is not affiliated with the other UBOs.

Determining the Benefit-In-Kind for the Employee

We begin by examining the “swap” by X BV. The 80% stake could either be contributed to Holding BV’s capital in exchange for new shares, or X BV could sell it to Topholding BV, which would then contribute it to Holding BV’s capital.[xvii] Parties opt for the latter, with Topholding BV remaining liable for the purchase price. Since X BV and Topholding BV are not related parties,[xviii] the agreed purchase price is, in principle, at arm’s length or commercially fair, representing the FMV of the 80% stake in OpCo 1 BV. Holding BV then issues 15% new shares to X BV, which fulfills its capital contribution by converting its receivable from Topholding BV into equity.

As Holding BV only holds shares in OpCo 1 BV and OpCo 2 BV, we can now deduce the value ratio between OpCo 1 BV and OpCo 2 BV.[xix] OpCo 2 BV is 4.3 times more valuable than OpCo 1 BV.[xx] Thus, it would be reasonable to reference Transaction 1 for payroll tax reporting purposes concerning Transaction 2. In other words, if the purchase price agreed in Transaction 1 was €100,000, one could confidently argue that the FMV of the in-kind income (Transaction 2) would be €27,083.[xxi] Therefore, the value of OpCo 2 BV is established through the third-party transaction involving OpCo 1 BV.

In this example, the FMV of the in-kind income is even somewhat flexible. X BV and Topholding BV can agree on any purchase price they wish. This doesn’t significantly impact X BV,[xxii] as the receivable is converted into a 15% participation regardless of its amount. Any agreed purchase price is, in principle, always commercial since they are not related parties. The fact that parties might become “related” after Transaction 1 (they won’t, see [xxiii]) does not affect this. If OpCo 2 BV seeks to minimize the payroll tax cash-out (related to Transaction 2), Topholding BV can agree with X BV to set the purchase price at €5,000. In that case, the in-kind income would be €1,354, while the employee’s personal holding would have acquired the same asset as in the scenario where the purchase price was set at €100,000.

4.2 When No Recent, Comparable Transaction Exists – The Truly Non-Marketable Share

If there is no 100%-relevant reference value, the FMV must be calculated separately. While one might estimate it, submitting a tax return requires accuracy, completeness, certainty, and no reservations, meaning an incorrect value could lead to a supplementary tax assessment or claim[xxiv], with potential penalties that increase in severity as the position becomes less defensible or substantiated.[xxv] Submitting an “incorrect” value can even be classified as a financial offense if intent or gross negligence is proven. Therefore, we always recommend creating (or having someone create) a well-supported valuation. Additionally, it can be helpful to seek advance confirmation from the Tax Authority on the FMV, which serves not only as a safeguard but also provides an opportunity to structure the transaction properly.

It’s important to remember that valuation is not an exact science; there isn’t only one correct valuation but rather a range of possible values. We often visualize this as a normal distribution — if the transaction were repeated an infinite number of times, what price range would form the norm? Essentially, the aim is to determine the most economically rational valuation, with all variables substantiated as thoroughly as possible. The good, the bad, and the ugly. We’ll explore this category further in this piece.

When tax motivations are the main driver, related transaction parties are inclined to argue for a valuation that yields the most favorable tax outcome for them. For deductible donations, FMV is then argued to be high, whereas for in-kind benefits and family gifts, FMV is argued to be low. For the Tax Authority, it’s the opposite. Although such fiscal interests shouldn’t influence valuations — given the required “accuracy” for tax filings and the Tax Authority’s role in pure law application — in practice, we often see the Tax Authority arriving at a lower deductible amount or higher taxable amount. Therefore, valuations must be neutral, objective, and accurate.

This also explains why the Tax Authority often involves the National Business Valuation Team (LBVT) in business valuations: this is a specialized branch of the Tax Authority with members who mainly have an economics or corporate finance background. Shortly after the LBVT was established around 2015, only a few individuals staffed the team, with whom I engaged in several intense and constructive discussions on valuation issues. The team has since grown to at least seven members, and their approach significantly influences the fiscal assessment of commercial valuation methods.

5. Which Recognized Valuation Methods Can I Use for Tax Business Valuation?

Preferably not: Rules of thumb, rough estimates, or “beer coaster” calculations.

There is substantial case law where the value of non-marketable shares was determined based on weighted average formulas, such as 1 x profitability value, 1 x intrinsic value, and 2 x yield value. However, this doesn’t imply that this specific formula always yields an acceptable valuation outcome, as such methods are “flawed.” This is the Tax Authority’s position,[xxvi] and ours as well. It doesn’t mean such methods cannot lead to a “correct” outcome, but if they do, it’s more a matter of chance than economic logic.[xxvii]

The Tax Authority refers to these as “accounting-based” valuation methods or “accountant’s formulas” because they are derived from the balance sheet or profit and loss statement for the taxable period or moment. Of course, it’s possible that two unrelated parties could enter a transaction where the purchase price is based on such an accountant’s formula, which would then, by definition, be a fair market price (i.e., FMV). However, this would represent a valuation approach not typically used in practice and thus not aligned with what would be applied if one assumed independent parties were negotiating. Accountant’s formulas are rare rather than dominant in commercial practice; only if such an accountant’s formula were to become the valuation standard in M&A (the “economic marketplace”) could FMV be determined based on that formula.

Preferable Approach: Prospective Methods Common in Corporate Finance

In practice, valuations tend to focus on the future: what cash flow can be expected from the investment? This involves the free cash flow that can be paid to the providers of capital. This focus is logical; a prospective buyer is far more interested in the future dividends they expect to receive from the shares than in past dividends that have already been paid out.

Consequently, valuation practice primarily uses methods tied to future cash flow, with the following two methods being the most common and, therefore, also the most tax-accepted:

– Enterprise Discounted Cash Flow (Enterprise DCF)

– Adjusted Present Value (APV)

Both methods discount future cash flows, so both technically qualify as “DCF” methods. However, the Enterprise DCF is most commonly associated with DCF, as it’s the standard approach in business valuations. We’ll therefore further (and simply) explain only this method.

6. Golden Standard: Discounted Cash Flow Method (DCF Method) – The Basics

6.1 For Which Companies is the DCF Method Suitable?

The discounted cash flow method, or DCF method, is best suited for valuing business units, projects, and enterprises where the intended capital structure (equity vs. debt) is clear and manageable. It can be challenging — even impractical — for very young companies without a commercial track record, as there is very little data to base projections on. The high risk associated with investing in such a company can, however, be reflected by applying a higher risk premium in the discount rate. That said, in the Venture Capital market (where investments are often in dreams, realizable or not), a DCF is rarely used. Instead, negotiations often focus directly on the cap table: the Venture Capitalist sees opportunity and potential in a target and wants to participate at X%, while the target’s shareholders aim to avoid excessive dilution. Typically, a DCF is not part of this process, or the DCF’s importance is quite low in such case.

6.2 How Does the DCF Method Work?

At its core, the DCF method works as follows: you create a projection of the company’s future performance and the resulting cash flow (forecast) it can generate. These cash flows are then “collapsed” into a single figure by discounting them. This figure represents the present value of future cash flows, known as the discounted (future, free) cash flows, or: DCF.

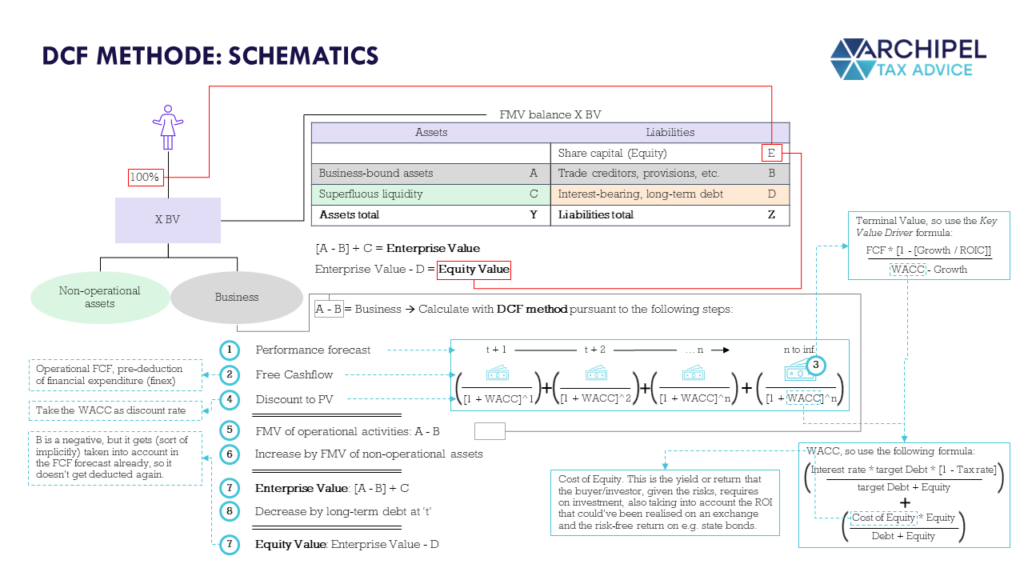

Side Note: Enterprise Value (entire business) vs. Equity Value (company without debt, with superfluous liquidity)

Before beginning a DCF valuation, it’s crucial to understand exactly what you want to calculate. Enterprise Value represents the entire business’ value, which is the value of its operational activities (determined through free cash flow) plus, according to some, the value of non-operational assets. These non-operational assets are not considered part of the enterprise value by all, however. The operational activities’ value can be calculated in a “FMV balance sheet” (not on a book-value basis but at actual value) by netting company-linked assets with company-linked liabilities (trade creditors, provisions, etc.). This balance corresponds to the amount produced directly from the DCF calculation after discounting operational cash flows and the Terminal Value. That’s why — after adding excess cash, etc., to reach the Enterprise Value — you only subtract the long-term/interest-bearing debt to arrive at the Equity Value, without deducting company-linked liabilities again. Those have already been netted in the DCF calculation itself. Enterprise Value thus pertains to all capital providers (both equity and debt), while Equity Value pertains solely to equity providers.

7. Components of the DCF Valuation

In the DCF method, the projected cash flows are discounted by both the cost of debt capital and the expected return for shareholders. So, what do we need for the DCF?

7.1: A Cash Flow Forecast for the Initial Years (10 – 15 years)

A crucial part of the DCF is forecasting the commercial figures, which must be as carefully and thoroughly substantiated as possible. This is not simply a mathematical exercise; it’s largely a job for the entrepreneur, who has the most informed insights into the company’s foreseeable future. However, an independent party can also take on the forecasting.

How far into the future should you look for the DCF? Ideally, a forecast period of 15 years is used, though periods of 5 to 10 years are more common in practice. This is partly because longer projections are more labor-intensive but also because uncertainty increases and accuracy decreases over time, reducing the forecast’s value. For companies with a stable commercial profile, historical figures provide a solid basis for the DCF forecast. In such cases, historical trends can often be extended into the future with reasonable accuracy to predict key ratios.

When analyzing historical figures, focus on free cash flow, Return on Invested Capital, and revenue growth, and then predict these metrics into the future. Ideally, you would also incorporate trends within the industry. However, in tax case law, judges have frequently deemed that extrapolating historical trends in commercial figures to the future can be a valid approach for developing projections.[xxviii]

The further into the future you project for the DCF, the less certain it becomes. Overemphasizing distant details can harm the calculation. For the first five years, work in detail, but after that, you can focus only on key commercial figures (Operating Revenue, Operating Costs, Depreciation, Operating Taxes, etc.). Reduced accuracy is less concerning because the discounted value of these future cash flows becomes significantly lower. Beyond a certain point, even a limited focus becomes too uncertain. This is where Terminal Value comes into play.

7.2 A Terminal Value for (Combined) All Subsequent Years

The Terminal Value (also called the Continuing Value) represents the value of future free cash flows beyond the forecast horizon. For example, if your forecast extends to 10 years post-valuation date, the Terminal Value reflects the business’ value starting from year 11 onward, theoretically continuing into “infinity.” Terminal Value often constitutes a significant portion of the total Enterprise Value.

There are two primary methods to calculate Terminal Value:

1. Key Value Driver Formula

2. EBITDA * Multiple Formula

7.2.1 Key Value Driver Formula for Determining Terminal Value (Theoretically Preferable)

The Tax Authorities, along with valuation theory, generally prefer the Key Value Driver formula, which is:

Terminal Value = FCF / [WACC – Growth]

Here, FCF (Free Cash Flow, or the free distributable reserve per year) is taken from the year immediately following the forecast period, and Growth is typically set at (at most) the inflation rate for the relevant country. This approach assumes that if your company grows faster than the national market indefinitely, it would eventually encompass the entire market, which is unrealistic. WACC (Weighted Average Cost of Capital) will be further explained in Section 7.4.

It’s important to note that this Growth rate can be different from the growth rate used to project FCF or to show the relationship between Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) and FCF. For FCF projections, foreseeable revenue growth can indeed be higher than national inflation.

The Key Value Driver formula is preferable because it considers the elements of Growth and ROIC (embedded in the FCF definition). These are essential factors since “value” is ultimately generated by the positive difference between Free Cash Flow and the investment required, adjusted for inflation and investment risk. Specifically, the conversion of revenue into Free Cash Flow is mathematically related to Growth and ROIC. The Free Cash Flow can be calculated by multiplying NOPAT by 1 – [Growth / Return on Invested Capital]. However, a drawback of this formula is that it works best when these two elements (Growth and ROIC) are constant, which is seldom the case.

7.2.2 EBITDA * Multiple Method for Determining Terminal Value (More Practical)

Due to the above complexity, the EBITDA * Multiple method is frequently used in practice, especially in M&A. Here, you take the EBITDA from the year after the last forecast year and multiply it by a factor (Multiple). The Multiple’s size depends on the company’s condition, the industry in which it operates, economic conditions, etc. These multiples are often maintained in databases by sector, year, and region — tracking, for example, how many times EBITDA an independent buyer typically pays in Country X for a business in Sector Y in Year Z.

From a commercial perspective a short-term investor who paid a purchase price based on the EBITDA * Multiple formula typically expects to recover their investment, with a return, within about five years. That return could logically come from increased EBITDA, a higher Multiple, or both. EBITDA can often be improved by cutting costs. A higher Multiple is often justified by the creation of synergy benefits achieved through a “buy and build” strategy, where the total enterprise expands. When the original buyer then wants to cash out their investment after five years, they can potentially realize a nice return. Numerous periodic M&A reports list the Multiples used each quarter by sector, providing transparency. However, for tax purposes (FMV determination in related-party transactions), we recommend using this formula more as a sanity check on the Key Value Driver formula, as the Tax Authority is more likely to accept it.

The resulting Terminal Value from the Key Value Driver formula (or any other formula used) is then discounted using the same discount rate applied to the Free Cash Flow (FCF) of the final forecast year.

7.3 Forecast of Free Cash Flows (FCF) – Clean Version of Cash Flow Forecast

Since we are calculating Enterprise Value, we focus first on the Free Cash Flow (FCF) generated by the company’s operational activities. As an interested buyer can influence the capital structure, only the cash flows from business activities matter. The key question is: what cash flows does the business itself generate for stakeholders?

After discounting, the value of non-operational activities is added. This means you’re not looking at commercial or taxable profit but at Operating Profit less Operating Taxes,[xxix] plus Depreciation, minus Increase in Working Capital, and CapEx (Capital Expenditures).

From Cash Flow to Free Cash Flow (FCF):

Operating Profit – Operating Taxes + Depreciations – Equity & CapEx Increase

The result is the Free Cash Flow (FCF), which is available for both debt holders and shareholders, as interest payments have not yet been deducted to arrive at FCF. This is known as the unlevered FCF to firm in practice.

You can also calculate FCF as follows as well:

NOPAT * [1 – [Growth / Return on Invested Capital]]

where Growth / Return on Invested Capital equals the Investment Rate, or the portion of FCF reinvested in the business. The amount invested in new assets or other areas cannot be distributed to shareholders.

If financing costs are deducted to determine FCF, you should then use only the Cost of Equity as the discount rate (see below) and directly arrive at Equity Value. In this case, you wouldn’t subtract the interest-bearing debt from the valuation, as the financing costs have already been considered.

The FCF is then discounted by a discount rate that increasingly weighs future cash flows more heavily.

7.4 The Discount Rate

The discount rate is ultimately the factor against which Free Cash Flow is discounted to determine what your company is worth today, considering capital costs, opportunity costs, and risks. So, how do you determine this Discount Factor?

Assuming unlevered FCF to firm, the cash flow is discounted using the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC).[xxxi] WACC is a weighted blend of the Cost of Equity (CoE) and the Cost of Debt (CoD).

As you project further into the future, forecasts become less certain. Therefore, cash flows projected in year t+3 (where “t” is the valuation date) are discounted more than those from year t+2 within the same valuation, reflecting increasing uncertainty.

The formula for WACC is:

[[Debt * CoD] / [Debt + Equity]] * [1 -/- Marginal tax rate] + [Equity * CoE] / [Debt + Equity]

The tax shield on debt is included in the WACC calculation, even though we didn’t factor it into the FCF calculation. This tax deduction on interest ultimately results in lower corporate taxes — meaning more cash flow for shareholders. This additional value is incorporated through a lower discount rate, which ultimately results in a higher valuation.

Cost of Debt (CoD)

The Cost of Debt (CoD) is essentially the interest rate applied to the target debt over the forecast period, with the target debt-to-equity ratio reflecting the proportions within the capital structure. Often, a 20:80 debt-to-equity ratio is used, but this can vary by company. Some companies rely more heavily on debt financing than others.

Cost of Equity (CoE)

The most challenging element in this formula is the Cost of Equity (CoE), as it typically varies by investor. An investor will require a high return on an investment with high (downside) risk to make the risk worthwhile. Otherwise, the investment would be unattractive given the potential for loss.

If the expected return (adjusted for risk) on a particular investment is lower than what the investor could reasonably achieve in, say, the stock market, they won’t proceed with that investment. In other words, an investment is usually made only if the Return on Equity exceeds the Cost of Equity.

In theory, the required return (or CoE) is determined using the following formula:

Risk-free rate of return + [Beta * [Market-rate of return -/- Risk-free rate of return]]

In this CAPM (Capital Asset Pricing Model formula, additional elements, such as a Small Firm Risk Premium, COVID Risk Premium, or other company-specific risk factors, can be added if applicable. Any factors that increase risk should be included to create an accurate risk profile. Beta accounts for sector-specific risk, reflecting the risk of the sector relative to the broader market. A Beta below 1 implies lower risk. Periodic reports are available that provide Beta estimates by sector. The “build-up” method of CoE is somewhat simpler, as you can simply add up the different risk premiums.

Due to the complexity of this approach, a more practical calculation sometimes used involves simply dividing free cash flow (after financing obligations) by equity. However, it’s important to note that the CoE generally reflects the investor’s cost, not that of the target company. Ultimately, though, the projected Return on Equity generated by the target must exceed the investor’s CoE for the investment to proceed.

7.5 So How Do You Apply the DCF Method?

The final calculations follow these steps:

1. Present Value of FCF + Present Value of Terminal Value = FMV of Operational Activities

2. FMV of Operational Activities + Value of Non-Operational Assets = Enterprise Value

3. Enterprise Value – Interest-Bearing Debt = Equity Value

4. This Equity Value can then be adjusted by well-supported amounts to reflect illiquidity, lack of transferability, lack of control, etc. These are known as Discounts (not to be confused with the Discount Factor or Discount Rate we discussed earlier).

With these steps completed, you have calculated the value of the share capital. Below is a schematic overview of these steps (with alternative numbering).

Schematic Overview:

1. Determine Free Cash Flow (FCF)and Discount Rate (WACC)

2. Calculate Present Value of FCF over the forecast period

3. Calculate Terminal Value and Present Value of Terminal Value

4. Add Value of Non-Operational Assets (if applicable)

5. Subtract Interest-Bearing Debt to obtain Equity Value

6. Apply Discounts for illiquidity, transferability, and control (as needed)

7.6 How Do the Tax Authorities View This?

As mentioned, the Cost of Equity (CoE) is the most challenging component of the WACC formula to determine. According to publicly available internal policy from the Tax Authority, a CoE above 15% is treated with suspicion and must be reported to the National Business Valuation Team (LBVT) by the inspecting officer. They view higher CoE as potentially leading to “suspiciously low” valuations. However, for young startups and other innovative business units, it’s not uncommon to use a discount rate above 18% due to the high risk associated with limited historical performance. In these cases, it’s essential to have thorough documentation to justify the rate. The LBVT has business valuation experts, so they understand the nuances involved.

According to the Tax Authority, CoE can be derived using the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) or the build-up method. As we noted, in practice, a third approach is sometimes used, which looks at the commercial figures of the parties involved.

The Tax Authority also prefers that Discounts (such as for illiquidity or lack of control) are not factored into a higher discount rate, given the sensitivity this introduces. Adding a 2% Risk Premium to the discount rate can create a significant impact if the calculated WACC without that premium is 5%. However, if the WACC were 15%, that same 2% premium would make a much smaller absolute difference.[xxxiii] We recognize this variability since the absolute impact differs substantially. This difference is illustrated in the following visual.

In summary, the Tax Authority recommends keeping discounts separate from the discount rate itself to maintain consistency in valuations. Adjustments should be justified and applied with caution, particularly in cases where high discount rates could be misinterpreted as artificially low valuations.

Therefore, apply a Discount “at the Bottom Line”. Or, as we, Dutch tax advisors, would say, extracomptabel (outside the accounting). The size of this discount also needs to be carefully determined. For example, the impact of a minority interest can be more significant in one case than in another. This is a matter of customization, where the total value of the discount would reflect what a third party would negotiate for the same share package. This justifies, in some cases, a separate valuation exercise.

8. Tip: Request Advance Approval from the Tax Authority on the Calculated Value if the Tax Interest is Significant; Obtain an Advance Tax Ruling (ATR)!

In principle, you can take a position on FMV in your tax return. However, if you do not align this with the Tax Authority in advance, you’ll never be certain whether they might challenge it in the near future. This uncertainty lingers for at least five years. For relatively small amounts, you might accept this risk. For larger transactions, it may be wise to proceed differently.

Your tax position in the return can be successfully challenged by the Tax Authority only if they present a more credible case than yours. In other words, the burden of proof is on them. The credibility of their case depends on the robustness of the supporting evidence for various variables. If they succeed in this, you would then need to “demonstrate” (a stronger standard than “make plausible”) that the Tax Authority’s assessment is incorrect.

To avoid such potential disputes, we often recommend obtaining an Advance Tax Ruling (ATR). This initiates a process where you consult with the LBVT (via the Inspector) to collaboratively determine the FMV. The Tax Authority’s Ruling Team typically engages in these requests, though it is not guaranteed that an agreement (settlement agreement) will ultimately be reached. In most cases, an agreement is achieved. This process can take around eight weeks and may incur advisory costs. However, this is the price of certainty — and ultimately, peace of mind.

That DCF valuation you made? Looks legit!

Long story short:

Do you have questions about your business valuation, or need advance certainty? Feel free to give us a call! This work is fascinating and provides you with insights into how your business creates value and what it could be worth. We’re here to help. At the bottom of this page, you can schedule an appointment with Pieter van Tilburg.

**[i]** Hoge Raad June 11, 2021, no. 19/04234.

**[ii]** Wage withholding tax serves as a prepayment on income tax, using similar brackets and rates with a top rate of 49.5%. However, wage tax has a different rate table for special rewards, like shares, which has a top rate of 55.5%. Although this higher rate does result in a higher withholding and remittance of wage tax, over the entire year, no more will be withheld than according to the regular rate table. Any excess wage withholding tax paid is refunded after the income tax assessment.

**[iii]** Article 13, first paragraph, Wet op de loonbelasting 1964.

**[iv]** Article 21, first paragraph, Successiewet 1956.

**[v]** Article 8b, first paragraph, Wet op de vennootschapsbelasting.

**[vi]** Initially on February 5, 1969 (no. 16 047), in relation to the now-abolished Wet op de vermogensbelasting 1964. Since then, the term has been further enshrined in various other laws.

**[vii]** Annex to the Proceedings II 1965/77 Parliamentary Question 939.

**[viii]** HR February 22, 1978, no. 18 674.

**[ix]** https://www.ad.nl/auto/eigenaar-geeft-drie-ton-korting-op-duurste-garagebox-van-nederland~a70d5893/.

**[x]** HR July 12, 2013, no. 12/02319.

**[xi]** Gerechtshof Amsterdam December 15, 2020, no. 19/01295 and 19/01298. This case involved a future, yet-to-be-approved zoning change and its relevance for valuation at the taxable moment. In this case, both the lower court and the court of appeal also expressed opinions on the valuation relevance of reference sales that occurred over four years prior and two years and seven months afterward. The question remains as to whether non-marketable shares (in general) are more susceptible to value fluctuations than real estate, which could mean the reference period for non-marketable shares should be even shorter. Note: this is a court of appeal decision. We are not aware of any cassation proceedings in this matter, although valuation cases are generally highly fact-based, leaving it to the lower court (such as the court of appeal) to determine what should be considered relevant for valuation. In our opinion, this decision has broad applicability.

**[xii]** Gerechtshof Arnhem-Leeuwarden July 10, 2021, no. 20/00906.

**[xiii]** Article 5b Algemene wet inzake rijksbelastingen.

**[xiv]** Articles 6.1, first and second paragraphs, 6.32, 6.34, 6.38, first paragraph, Wet op de inkomstenbelasting 2001.

**[xv]** Hoge Raad November 10, 2017, no. 17/00841.

**[xvi]** It is worth noting that the heirs of the family could also have sold the painting for more money than they will now receive through the income tax deduction. So, from their perspective, this is still a generous gesture. However, this is not how it is portrayed in news reports, which mainly focus on what the “state treasury” is now missing out on rather than the “impoverishment” of the heirs.

**[xvii]** A direct sale to Holding BV, whereby Topholding BV gives a portion of its shares to X BV, is also possible, but it is less illustrative for our example.

**[xviii]** Article 8b, first paragraph, Wet op de vennootschapsbelasting 1969.

**[xix]** After all, 15% in Holding BV is evidently worth as much as 80% in OpCo 1 BV. The 15% stake in Holding BV is also equivalent in value to (indirectly) 15% in OpCo BV 1 plus 15% in OpCo 2 BV. Therefore, 80% in OpCo 1 BV is equal (in value) to 15% in OpCo 1 BV plus 15% in OpCo 2 BV.

**[xx]** X BV has “exchanged” 65% in OpCo 1 BV for 15% in OpCo 2 BV. Fifteen percent corresponds to 65% in a ratio of 1 to 4.3.

**[xxi]** €100,000 represents the value of 80% in OpCo 1 BV, meaning that 100% of OpCo 1 BV amounts to €125,000. OpCo 2 BV is worth 4.3 times as much as OpCo 1 BV, which totals €541,667. Five percent of this is €27,083.

**[xxii]** In theory, Topholding BV and Holding BV could refrain from further transactions with X BV following the sale, which would prevent X BV from obtaining the 15% interest, so this (roundabout) route is not entirely risk-free.

**[xxiii]** Hoge Raad September 26, 2014, no. 13/02261, and Hoge Raad December 18, 2015, no. 15/00942. Both rulings concern “relatedness” in the context of the arm’s length loan doctrine but have, in our view, broader implications.

**[xxiv]** Articles 16 and 20 Algemene wet inzake rijksbelastingen.

**[xxv]** Articles 67a – 67f Algemene wet inzake rijksbelastingen, in conjunction with Besluit Bestuurlijke Boeten Belastingdienst.

**[xxvi]** Freedom of Information Act-released internal policy of the Tax Authority: https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/wob-verzoeken/2020/07/14/besluit-op-wob-verzoek-over-documentatie-van-het-business-valuation-team-van-de-belastingdienst-over-de-waardering-van-aandelen-van-bestaande-bedrijven-en-start-ups, p. 25.

**[xxvii]** Gerechtshof Amsterdam June 20, 2003, no. 02/04164.

**[xxviii]** See, for example, Gerechtshof Amsterdam December 22, 2011, no. 08/00073.

**[xxix]** Also known as NOPAT: Net Operating Profit After Taxes.

**[xxx]** This interim result is called the “gross cash flow.”

**[xxxi]** Weighted Average Cost of Capital.

**[xxxii]** To discount a forecasted cash flow from year t+1, you divide it by \([1 + \text{discount rate}]^1\). For year t+2, you divide the relevant cash flow by \([1 + \text{discount rate}]^2\), etc. The general rule is: the more accurate, the better, so ideally, you would forecast and discount on a monthly rather than an annual basis.

**[xxxiii]** Internal Tax Authority policy, p. 31.