Download this article in pdf here.

In the Netherlands, all costs incurred by a business enterprise are initially deductible from the taxable base in the Corporate Income Tax (CIT), as Netherlands-based companies are deemed to run a business enterprise with all of their assets and liabilities. This is different only if a legal provision limits or prohibits the deductibility.

There are many limitations of cost deductibility, ranging from general shareholder influence elimination and transfer pricing rules to specific cost exclusions. Depreciation caps are present as well, although they cause only temporary differences between the commercial and fiscal books.

But we want to zoom in specifically on wage costs. Labor costs are inherently business-driven costs that -as such – do not fall within the scope of a deduction limitation. However, the CIT Act (CITA) contains a provision, article 10-1-j (the Article), that restricts deduction of the issuance or grant of shares or Stock Appreciation Rights (SARs) to employees. The current wording of the Article is effectively as follows.

“Non-deductible are the issuance or grant of shares in the capital of that company or an affiliated company, as well as the issuance or grant of rights to buy stock or profit rights in that company or an affiliated company, as well as the issuance or grant of rights that are similar/equivalent to the beforementioned shares or rights, explicitly including rights -allotted to employees having earned more than €589,000 taxable wage in the previous year- of which the value is for ≥70% directly or indirectly determined by the value increase of those shares or profit rights.”

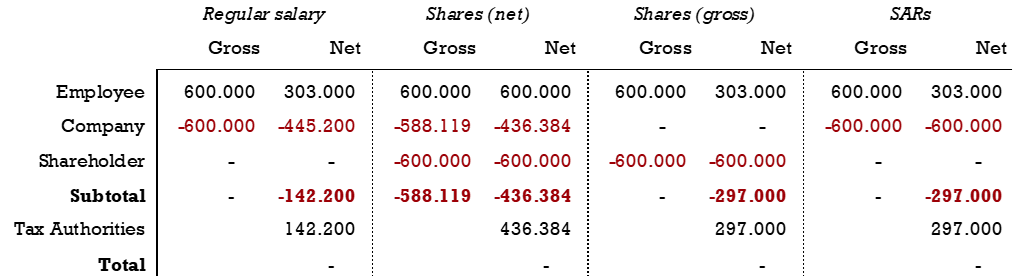

We will look specifically at the deductibility of the Wage Tax component relating to the issuance or grant of shares or SARs to employees. To better construe our views, we walk you through the Wage Tax and CIT aspects of (i) regular salary, (ii) shares as wage and (iii) SARs.

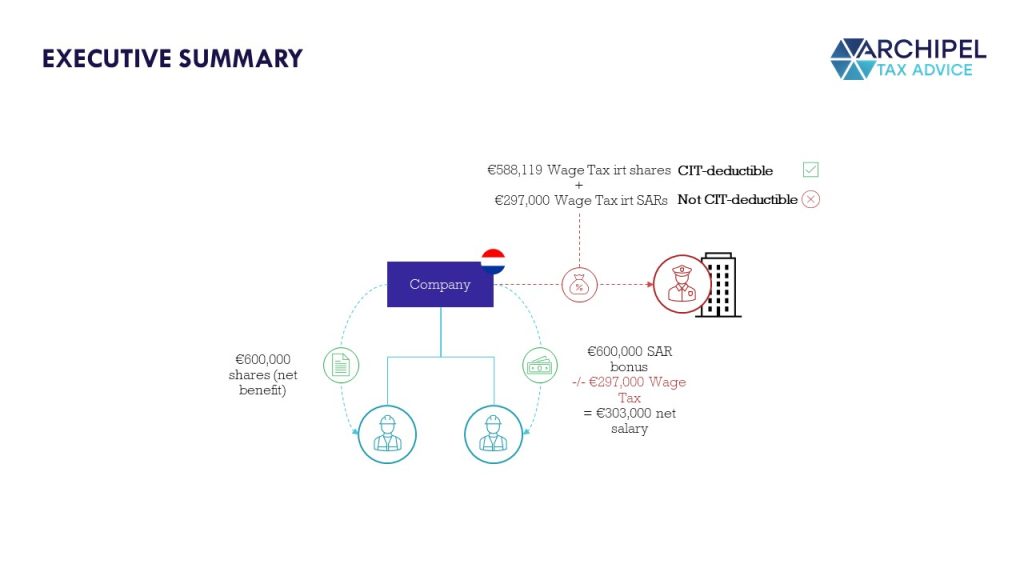

Executive summary

A Netherlands-based company issuing or granting:

- shares in its capital to an employee, may deduct from its CIT base the Wage Tax component related thereto (which is the case if the shares are granted/issued on a net basis).

- SARs to an employee, cannot deduct from its CIT base the Wage Tax component related thereto (if that person’s taxable wage in the preceding year exceeded €589,000).

Executive Summary translation to Dutch

Voor de vennootschapsbelasting (VPB) zijn bruto loonbestanddelen aftrekbaar, tenzij de aftrekbaarheid ervan is beperkt door bijvoorbeeld art. 10-1-j Wet VPB 1969. Daarin staat dat de toekenning of uitgifte van aandelen, aandelenoptierechten, winstbewijzen niet aftrekbaar is van de VPB-grondslag, en ook dat Stock Appreciation Rights (SARs) niet aftrekbaar zijn van de VPB-grondslag indien de totale fiscale loonsom van de desbetreffende SAR-houder in het jaar ervoor méér was dan €589.000.

Je kunt je afvragen of deze aftrekbeperking enkel bovengenoemde nettoloonbestanddelen betreft, of dat ook de loonbelasting die is verschuldigd over bovengenoemde loonbestanddelen is uitgesloten van aftrek.

Mijns inziens geldt voor SARs dat het loonbelastingelement (mits de €589.000-grens is overschreden) niet aftrekbaar is, maar voor aandelen(opties) wel. De loonbelasting die is verschuldigd over de toekenning/uitgifte van aandelen(opties) aan werknemers is in principe aftrekbaar voor de VPB, maar dan moet die loonbelasting wel de werkgever ‘raken’ (ook al drukt de loonbelasting wetstechnisch op de werknemer).

De loonbelasting raakt de werkgever alleen maar bij een (al dan niet gehele) netto-afspraak waarbij de werkgever het alsdan nettovoordeel dient te bruteren en de daaruit voortvloeiende loonbelasting aan de fiscus afdraagt. Bij een bruto-afspraak houdt de werkgever de loonbelasting in op het cash-gedeelte van het brutoloon, en als dat niet volstaat, kan de werkgever de loonbelasting in theorie verhalen op de werknemer. Dit is de standaardsituatie (zie ook artikel 27-4 Wet op de loonbelasting 1964).

Bij naheffingsaanslagen voor te weinig betaalde loonbelasting is het voor de werkgever in de praktijk echter vrijwel onmogelijk om die belasting te verhalen op de werknemer, omdat dan vaak sprake is van eindheffing (artikel 31 Wet op de loonbelasting 1964) die per definitie voor rekening van de werkgever komt. Voor een succesvol verhaalsrecht moet de werkgever allereerst een verzoek om een verhaalbare naheffingsaanslag doen, waarna -bij eventuele litige- de civiele rechter die vordering ook nog eens moet toewijzen (waarna verrekening met het te betalen loon zou plaatsvinden). En bij dat laatste station kan het zomaar eens erg lastig worden, omdat de vordering alleen wordt toegewezen als sprake is van ongerechtvaardigde verrijking of onverschuldigde betaling, welke rechtsfiguren weer hun eigenaardige vereisten kennen.

Assumptions, examples and analyses

For clarity’s sake and to better focus on the CIT-Wage Tax relationship, let’s assume the following parameters:

- The CIT has a flat rate of 25,8%,

- The Wage Tax has a flat rate of 49,5%,

- There is no Personal Income Tax (PIT),

- There are no social security and national insurance premiums, and

- Salary is paid out annually instead of monthly.

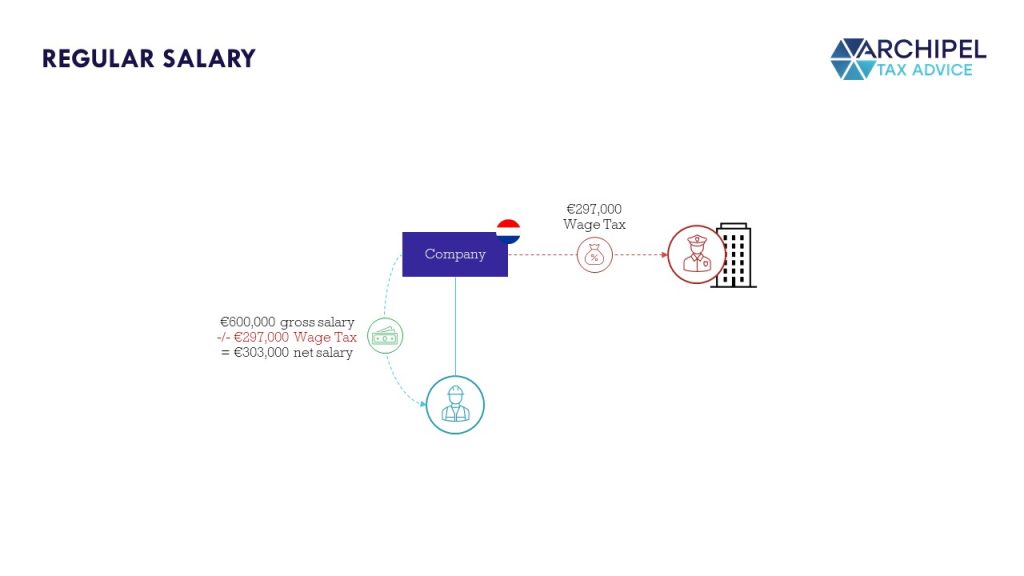

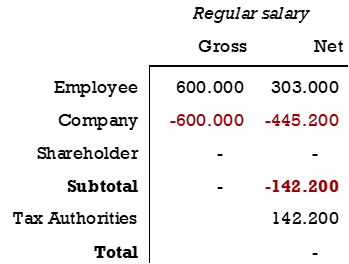

Regular salary

In year X a Dutch company annually pays a key employee €600,000 gross salary. The company withholds €297,000 Wage Tax and pays that amount to the Tax Authorities. The remaining net salary of €303,000 is paid out to the key employee.

For the company, the gross amount of the salary, being €600,000, is deductible from its CIT base. That means that the company’s net cost of paying out that salary is €445,200 instead of €600,000.

As for the Tax Authorities, they first receive €297,000 in Wage Tax, but subsequently ‘give back’ €154,800 in CIT, netting €142,000 in tax collections.

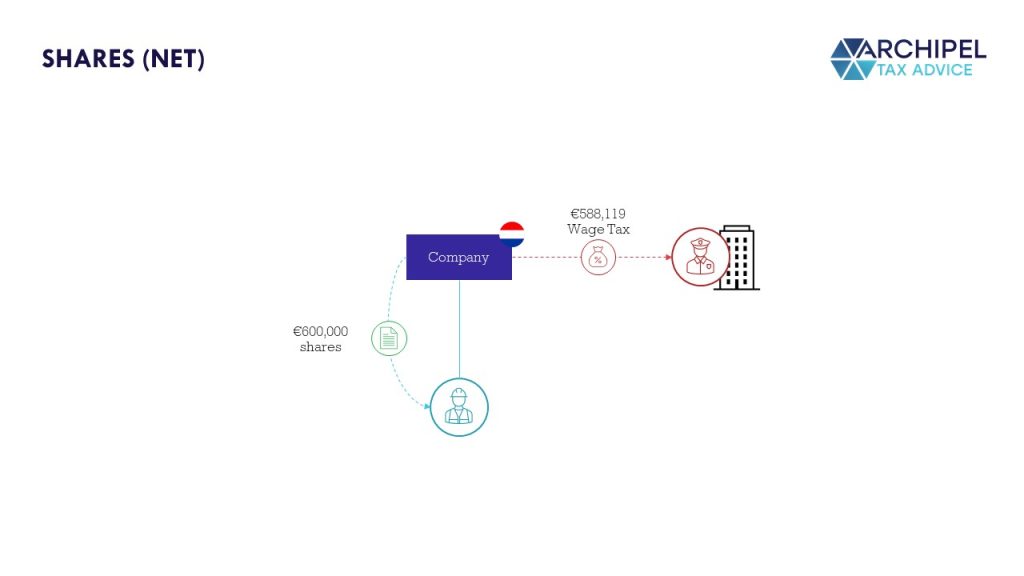

Shares

In year X+1, that same company decides that that same key employee should receive shares in the company’s capital, instead of a regular salary, against a contribution of the nominal value being €0,10, which we disregard for simplicity’s sake. An Enterprise Discounted Cash Flow calculation has determined the Fair Market Value of the shares involved to be €600,000.

Under the Wage Tax Act[i], such shares constitute wage-in-kind for the Fair Market Value thereof at the time of the key employee obtaining (legal or economic) ownership, being €600,000. This means that the company should ‘withhold’ and pay Wage Tax to the Tax Authorities on the shares that it issues to its key employee. Exactly the same goes for a transfer of existing shares from the main shareholder to the key employee.[ii] For CIT and Wage Tax purposes, there is no difference between these alternatives.

But how can the company withhold Wage Tax on shares?

Let’s look at it this way: in order to directly purchase the shares, the key employee would have to have earned €600,000 net salary, meaning a gross salary of €1,188,119. Of that gross salary, €588,119 would have been Wage Tax to be withheld and paid to the Tax Authorities. Applying this to the example at hand, the company therefore has to pay €588,119 to the Tax Authorities. The same goes for the alternative route in which the company’s shareholder had granted shares to the key employee. This is called the ‘grossing up’ of the net wage-in-kind.

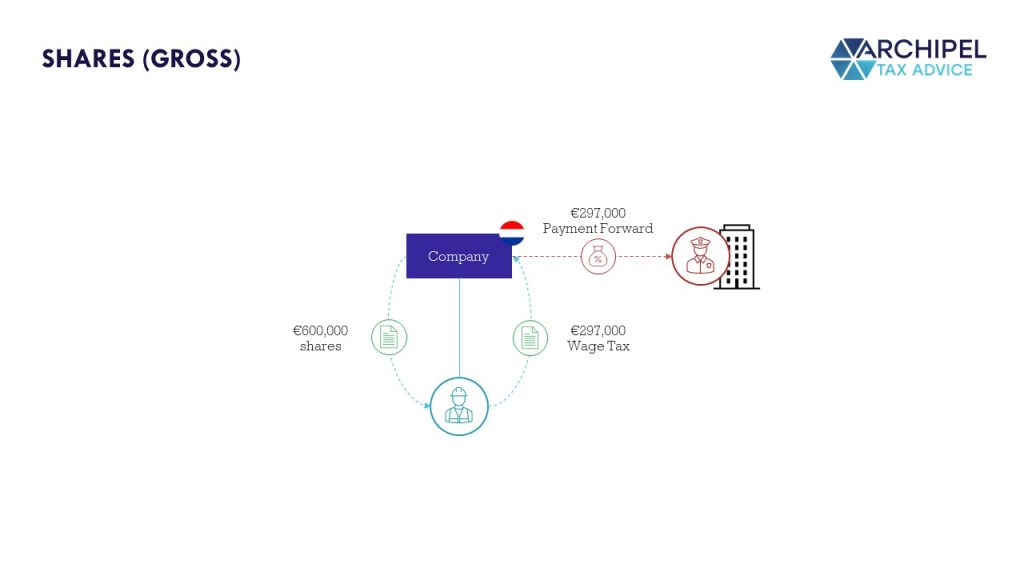

Another scenario, however, is that the shares are not granted/issued on a net basis, but on a gross basis. In that case, the company exercises (non-litigative) recourse against its key employee. The key employee pays €297,000 (e.g. from its regular €600,000 gross salary of year X) to the company, which the company then forwards to the Tax Authorities. That way, the net benefit relating to the shares is limited to €303,000.

This begs the question whether or not the company can deduct that gross wage-in-kind from its CIT base, just like regular salary. If not, the situation would be as follows.

Under the Article, the issuance or grant of shares in the company’s (or an affiliated company’s) capital is not deductible. This makes sense, as the issuance or grant of the shares to the key employee does not affect the company’s P&L or balance sheet, especially when there is no contribution involved. It only dilutes the main shareholder.

However, one might argue that because the contribution is nil, the company has foregone share premium, which it would otherwise (when issuing shares to other parties) have received, and that this never-received cash influx should qualify as business costs. The result would be symmetrical: a CIT deduction versus a Wage Tax addition.

A brief legal history of CIT-deductibility of stock (option rights) issued/granted to employees

This was the case made by an employer a long time ago, regarding FY 1951/1952, in which case the employer had issued shares to two of its directors at par value. The Tax Authorities took the position that the Fair Market Value was higher than the par value, and that the difference was taxed with Wage Tax. The employer then took the abovementioned position. In 1956 the Supreme Court ruled[iii] that the foregoing of share premium is not the same as sacrificing profit, and therefore that the difference between the par value and the Fair Market Value was not deductible. It then went on and ruled that the issuance of shares by a company -when foregoing share premium- does not decrease its profit, but only caused a lower equity influx, because the issuance of shares does not affect a company’s P&L.

This begs the question whether or not the Wage Tax costs incurred by the company relating to the issuance or grant of the shares are CIT-deductible.

If we dissect the above judgment, we conclude that the Wage Tax costs that the company incurred due to the share issuance are deductible. There are strong indications for this view. The Supreme Court only referred to the difference between the par value and Fair Market Value, being the net benefit actually received by the employees. In the end it refers to a lower equity influx, which clearly does not take into account the Wage Tax payable by the company, as that Wage Tax results in an actual cash-out and equity decrease.

Some time after the 1956-judgment, in 1996, the Supreme Court even changed its mind[iv] on this subject matter, by ruling in a new case regarding FY 1990 that all types of wage(-in-kind) qualify as deductible business costs. Although it shouldn’t have impacted the Supreme Court’s views, it seems to much of a coincidence that on November 1, 1993, the legislator had overruled the Supreme Court’s 1956-judgment by explicitly allowing for the deduction of share issuances and grants to employees.

Be that as it may, in 2007 the Supreme Court’s 1956-judgment was legally reinstated by way of (part of) the Article, fully restricting the deduction of shares (and stock options) issued or granted to employees. As mentioned above, this deduction restriction covers shares in the capital of the employing company as well as of group companies, but also stock option rights, profit rights “and similar/equivalent rights”.

According to the parliamentary history[v], the rationale behind this restrictive change, apart from State Budget enlargement, was fueled by the view that it’s not the company, but only its shareholders that get poorer, when shares are issued or granted to employees (at a purchase price or contribution of nil). Shareholder costs versus business costs.[vi] Not long before this change, the arm’s length principle had formally entered the CITA, effectively eliminating shareholder influences from the taxable profit calculation, which may have been a factor in enforcing this new piece of legislation.

The taxed (Wage Tax) versus non-deductible (CIT) asymmetry was clearly not seen as an issue, as ‘symmetry’ had already been achieved by way of other ‘Box 3’ shareholders of such company being able to report a lower taxable base, and ‘Box 1’ shareholders (which are quite rare) may deduct the value decrease from the PIT base. The legislator explicitly stated its intention to return to the regime as ‘devised’ by the Supreme Court in 1956. And as we mentioned above, the Supreme Court left open the way for deducting Wage Tax costs that are incurred by the company. Justifiably so: they are business costs.

Back to our example regarding shares

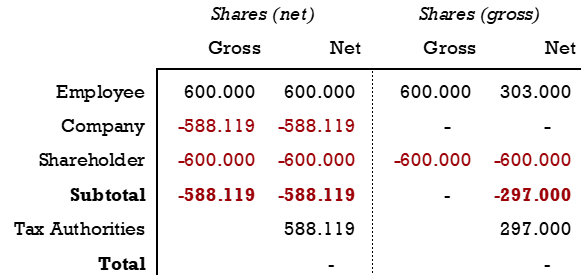

This analysis results in the following table.

Please note that the ‘gross basis’ alternative does not differ from the table in which Wage Tax costs were assumed non-deductible. This may seem strange, but it makes sense when you think of the recourse that the company exercises against its key employee. When the employee pays -in cash- 49,5% of the shares’ Fair Market Value to the company, that cash was already earned by that key employee through his regular salary in year X. And that gross regular salary had already been deducted from the company’s CIT base in year X. Therefore, another deduction in year X+1 at company-level would result in a double deduction for a one-time business cost. In the ‘gross basis’ alternative, it is the key employee that incurs the Wage Tax cost.

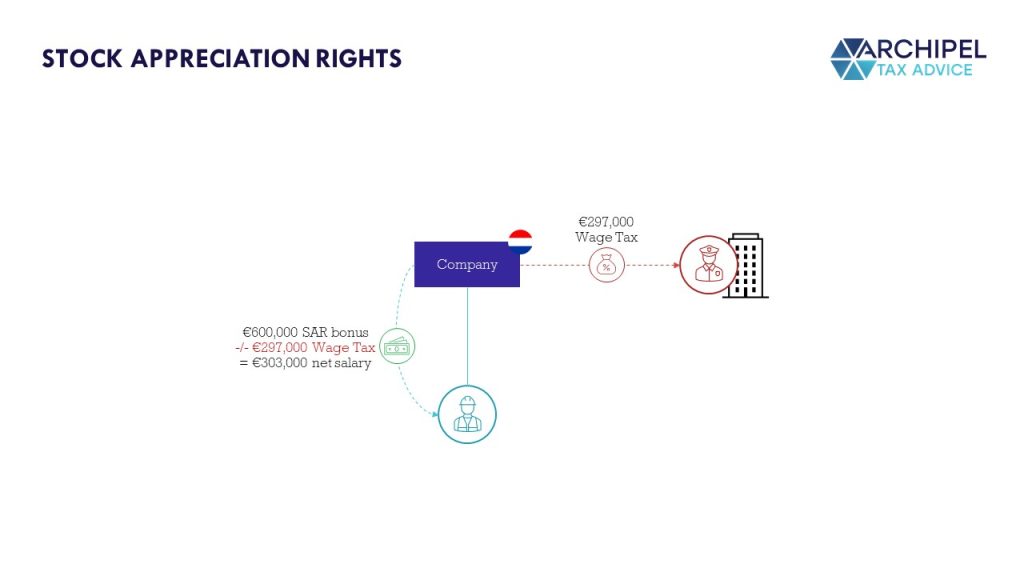

Stock Appreciation Rights

So now that we’ve concluded that (option rights to buy) shares issued or granted to employees are not CIT-deductible (but the Wage Tax cost incurred by the company is), the savvy employer could think of an instrument that is fully CIT-deductible with which the key employee can profit from the company’s value increase.

Let’s say that the same company from our previous examples decides, in year X+2, to remunerate the same key employee with a SAR instead of shares, that the gross bonus pay-out amounts to €600,000, and that the taxable wage of the key employee in the previous year exceeded €589,000.

A bonus payment, like regular salary, is in principle fully deductible. However, in case of SARs, an exception was made to prevent the circumvention of the non-deductibility of share grants/issuances.

A brief legal history of CIT-deductibility of SARs issued/granted to employees

Following the entry-into-force of abovementioned 2007-legislation, a worry (also noticed in tax literature) gained momentum that employers would circumvent this rule by remunerating their employees by way of a bonus of which the amount was determined by the company’s share value increase between two points in time, which bonus was fully deductible. This worry was fueled by both the legislator’s[vii] and the Deputy Minister of Finance’s[viii] expressed views that a SAR was not a right “similar/equivalent to shares, stock options rights, or profit rights”, and therefore was not covered by the ex tunc wording of the Article.

In reaction to that worry, as from 2009 the legislator explicitly included SARs within the scope of the Article, but only if the taxable wage of the employee involved in the previous year exceeded €500,000 (currently €598,000). That threshold has the restriction focusing solely on (deemed) excessive remunerations.[ix]

As with shares, this begs the question whether or not the Wage Tax costs incurred by the company relating to the issuance or grant of the SARs are CIT-deductible.

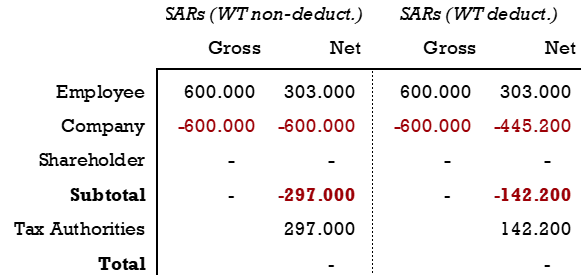

Back to our example regarding SARs

The two possible CIT treatments are as follows.

The difference comes down to the CIT-deductibility of the Wage Tax component relating to the SARs. Looking at the Article’s wording in a grammatical sense, it is the ‘issuance or grant of a SAR’ that is non-deductible. As with regular salary, the employee has a ‘right’ to a certain payment. That payment is in principle always the gross payment. The SAR itself is the gross instrument, not just the net benefit for the employee.

This view is strengthened by the fact that the CITA regards the SAR from the company’s perspective, which is on a gross basis. Furthermore, the SAR-restriction entered into force synchronously with other ‘punitive’ measures fiscally discouraging excessive remuneration of employees[x], right when the global financial crisis provided additional momentum for governments to increase taxes to sponsor the State Budget. Within this frame, it is highly illogical to interpret the Article in a way that the Wage Tax component relating to a SAR is deductible.

Difference between CIT treatments of shares and SARs

As mentioned, it is one and the same provision that restricts the deduction of both shares and SARs issued or granted to employees. It therefore may seem inconsistent that for shares the Wage Tax component is deductible, but not for SARs. However, our view stands.

The deduction restriction refers to ‘shares’ but not the Wage Tax costs relating thereto. From a grammatical point of view, shares don’t include the Wage Tax costs associated with them. Shares are just shares, whereas a bonus payment is always interpreted on a gross basis (i.e. including the associated Wage Tax costs).

Another example

Let’s strengthen this by an example. Say that in year X+3 the company from our example decides to remunerate its key employee in two types of wage: regular salary of €588,119 and shares with a Fair Market Value of €600,000, totaling a gross taxable wage of €1,188,119.

As we’ve explained before, the key employee is subject to Wage Tax, which is withheld and paid to the Tax Authorities by the company, being the withholding agent. One of the existential reasons for the concept of ‘grossing up’ is that the Tax Authorities collect taxes in cash only. The total Wage Tax cost amounts to €588,119, which can be withheld from the €588,119 regular salary component. The remaining net wage that the key employee receives is €600,000, consisting of the shares.

When looking at it that way, the gross regular salary component (€588,119), also being the entire Wage Tax component, is CIT-deductible, and the share component (€600,000), also being the net benefit, is not. This situation is effectively the same as the abovementioned share example in which only shares with a Fair Market Value of €600,000 were issued, which was subsequently grossed up. We see no reason for these two situations to be treated differently in terms of CIT-deductibility.

Conclusion

Wage Tax costs that cause a cash-out (and equity decrease) at company-level, are CIT-deductible, unless they relate to SARs covered by the Article. This means that Wage Tax costs relating to the issuance or grant of shares or stock option rights to employees, are CIT-deductible, despite what one might think when reading the wording of the Article.

This is due to the differing natures of SARs (gross cash bonus) and shares (non-cash element) in combination with a grammatical interpretation of the Article, the spirit of the law as expressed in the parliamentary history, and the 1956-judgment from the Supreme Court leaving open the way for CIT-deductibility.

This leads us to the following overview.

Download this article in pdf here.

Any questions or want to discuss?

Feel free to book a time below – it’s on the house!

[i] Articles 10-1 and 13-1 of the Wage Tax Act 1964.

[ii] For reference, please look at Supreme Court, November 1, 2000, ECLI:NL:HR:2000:AA7993 and Supreme Court, January 12, 2022, ECLI:NL:HR:2022:15.

[iii] Supreme Court, June 20, 1956, BNB 1956/244.

[iv] Supreme Court, October 16, 1996, BNB 1997/47.

[v] MvT, Kamerstukken II 2005/06, 30 572, nr. 3, p. 28–29, 47-48.

[vi] We know this not to be true, however, because the Wage Tax costs so triggered do make the company ‘poorer’, and therefore are not shareholder costs.

[vii] NV, Kamerstukken II 2005/06, 30 572, nr. 8, p. 67.

[viii] Decree of May 30, 2001, nr. RTB2001/1738.

[ix] For reference, please look at Nader gewijzigd amendement-Tang en Cramer ter vervanging van dat gedrukt onder nr. 73, Kamerstukken II 2008/09, 31 704, nr. 74.

[x] Article 3.92b of the PIT Act 2001.